Graphene inventor Vivek Koncherry: from ‘backwater’ to space inventor

Applications Collaborations Graphene Engineering Innovation Centre 1st May 2022

In January 2022, Graphene Innovations Manchester became the latest Tier 1 partner of the Graphene Engineering Innovation Centre at The University of Manchester. Led by UoM alumnus and graphene inventor Vivek, the company uses advanced manufacturing techniques to deliver composite material applications for now and for the future. We sat down for a chat and started back at the beginning, in rural India…

What were your first touchpoints with science and technology?

I’m originally from Kerala in India, where there are a lot of lagoons and lakes and the area is literally called ‘Backwaters’ (pictured below). So I come from a small village background, where my family made flooring and carpets from natural products like coconut fibre.

Even though the company’s core business was flooring, my father used to experiment with new business all the time. He used to make electronic devices and I worked with him when I was a kid, so he taught me about magnets and batteries and how to make a magnet with a nail and a few copper coils. This was when I was in primary school.

So I was interested in new research from a young age but I was still in the village and there was a limit to what was available, so I didn’t have all the opportunities for what I wanted to do. I always had a feeling for invention – I wanted to invent something but didn’t know how.

So what happened after primary school?

I continued through high school in India, but then came to Manchester to do my undergrad in 2001. Basically, my family sent me to the UK to learn textiles and benefit the family business. And while I was here I realised that the field of textiles in the UK had moved to a higher level than I knew and the same weaving machines that I knew could be modified to weave carbon fibre. That was my first exposure to an old technology that could be modified to a new use, making composites for aircraft and automotive etc.

My degree was joint between textiles and business, so I had some business training was well, but my projects moved into the area of natural fibre composites. So when I finished my undergrad, I went back to India to the family business.

So that could have been your Manchester story finished…

I had no plans to come back – I was very good at my job and I was happy doing it. But then in 2009 the recession happened and people stopped spending on home furnishings. They had other priorities: food, clothing. So home furnishing was struggling and I decided to come back to Manchester and work on composites.

What were you working on?

I got sponsorship for a PhD to work with [car manufacturer] Bentley, who wanted to coat nanomaterials onto carbon fibre. But there wasn’t a machine to do it. So I started building the machine to do the process. This is the link back to my father tinkering with electronics – now I was making the machine to fix a specific process problem.

I should say, it wasn’t just me building the machine. In Manchester there are professors with lots of experience who guided me – plus electrical technicians, mechanical technicians, lots of knowledge there. It’s an ecosystem. So I’ll never say I did it all by myself. There were lots of people behind me.

I realised very young that the supply chain – whether that’s material or knowledge – is all about people. And that’s the same for this company now, working at the GEIC. It’s the whole of the system and the people in it that makes it strong.

Something you learned from your early days in the family firm?

Yes, because in a village how it operates is that you don’t have massive factories. You have a cottage industry and small suppliers who are making things in their homes. All of a sudden you are managing a lot of people.

For example, if you’re making a doormat and you want to fill a 40ft container for IKEA, you need to employ thousands of people. For one Walmart order, you would need 10,000 people. As a child I knew these kinds of scaling. And people don’t always get this right – they think scaling is a gigafactory or something like that. It’s not true all the time.

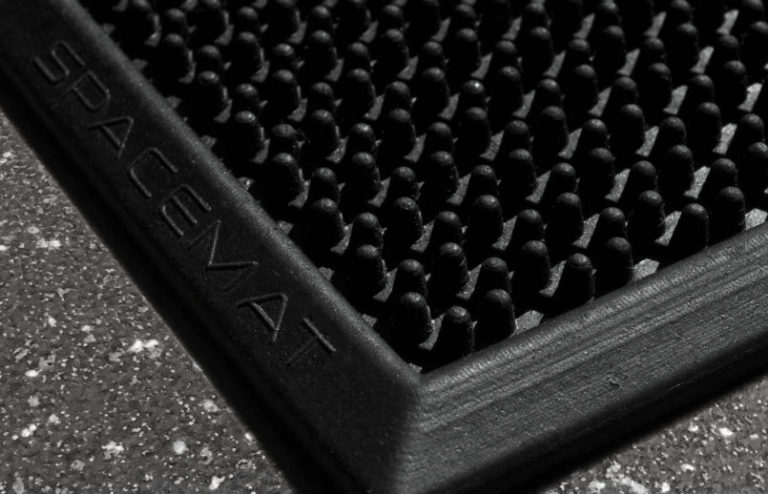

Sometimes scaling means a large supply system. Hundreds of small companies around Manchester, say, is equal to a gigafactory and because they own their companies, they’re more motivated to make it work. That’s what I did with SpaceMat: instead of pouring millions or hundreds of millions, into one factory, I went with the small players instead and asked each of them to do one small thing.

So tell us about SpaceMat, your recycled rubber product…

This is a bit of a jump ahead because after my PhD I worked for eight years as a post-doc in the Department of Materials in Manchester.

After Bentley I got a project from the Government’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) in materials – at this point I now had the knowledge to build machines and robotics – and then also had a lot of projects through the university from Innovate UK and EPSRC, all for carbon-fibre composites.

Most of the time I was different because I brought the automation side to it and also brought that textiles expertise that might have been lacking among other engineers. I also started getting into artificial intelligence and internet-of-things and I won a competition run by EPSRC in 2019 on AI/IoT .

So eventually I had textiles, materials, robotics, AI/IoT coming together and it started forming into a shape. I didn’t really have any plans to start a business, but when I was speaking to James Baker [CEO of Graphene@Manchester] and told him about the recycled rubber mat I was developing with graphene, he was the one who told me – this should be a business. And he said he would try to support it through the Graphene Engineering Innovation Centre (GEIC).

What interested you in recycled rubber?

I had some background knowledge of natural rubber. We don’t just have coconut trees in Kerala, we have rubber plantations as well. And then a few years ago I read an article about the UK shipping waste tyres to India. Every day, there were around 100,000 tyres coming off UK cars and most of them being shipped abroad.

At the same time, something like 2 million Indians die because of air pollution, so I wondered if there was anything we could do. I’d seen some papers with evidence already out there about how graphene benefits rubber. So what I did was to take the waste car tyre, chop it up, mix it with some natural rubber and graphene – there are some proprietary processes in there as well – and the new mat was five-times better in terms of its mechanical performance than anything else in the market made with recycled rubber.

GEIC tested it compared to other mats to show its benefit compared to synthetic binders like polyurethane. Instead I used some virgin rubber, which is renewable, as the binder, and the added mechanical strength of the graphene transformed its performance.

How have you found the experience of turning SpaceMat into a business?

Without the GEIC, the business wouldn’t have happened. It’s not easy to grow a new business when you also have a full-time job as a post-doc. But with the Bridging the Gap programme at the GEIC, I was able to tap into a lot of capabilities in the GEIC. And it didn’t just help me with the technical side but also helped me spread the news, to get the word out there. That is how investors found me.

It’s really important to be visible at shows like Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week and the Advanced Engineering Show. That’s what has given me a platform and enabled me to attract investment.

It’s quite a leap from rubber mats to a graphene space habitat…

I started from the floor, graduated to a car, to a plane with DSTL and BAE Systems and then the next step is space!

What’s important to understand is the idea of rapid research. You could choose to do a 20-30 year programme to make a space habitat, qualifying every single aspect, but by the time you invent that thing, most of the materials are outdated.

For example, the James Webb space telescope that was launched recently – they started work on that 20 or 30 years ago. Graphene didn’t exist, carbon fibre wasn’t even in the mainstream – things are moving so fast with other 2D materials, MXenes and so many applications… we need to do things faster.

So instead of making everything perfect, you make an educated guess, make a small prototype and send it into space with sensors. Then you know which part failed. I’m not saying everything will work from day one – some of the components can and will fail. But if you want rapid research, the only way is to make something really fast, test it, get the data and learn from it. This what Elon Musk does, or Richard Branson on Virgin Galactic – they’ve had crashes and rocket failures, but every time they’ve gone forward much faster.

What’s the key to commercialising a good idea?

Personally, I don’t just do it for the sake of commercialisation. When I make a fully finished product, I just feel good. It’s like a drug. And then you want to feel more of it. I see a good product as a piece of art – I can look at it for hours. And the same with other students producing things – I guess it comes from textiles, which has that art/science crossover, but I definitely see the ‘art’ in manufacturing.

The space habitat images are certainly striking. How did they come about?

When I had the initial idea [to design a space habitat for the 2021 Eli Harari competition], I contacted a lot of different companies and agencies working in this area to get feedback. I was contacted by global architect firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM). With their design expertise, led by Daniel Inocente, and my materials and manufacturing knowledge, we came up with the concept of Graphene Space Habitat. Previously, the European Space Agency, SOM and MIT had done work on a moon village project, but after talking with me and the GEIC, they said they would design something new for this competition.

And you won!

Yes! It was an ambitious entry. But I think you need to be ambitious with innovation and advanced materials.

And what about Graphene Innovations Inc – how did you make that connection?

Adrian Nixon [editor of the Nixene Journal] introduced me to Mark Diamond [GII Chairman] a couple of years ago. Mark is connected to Tom [Hirsch, CEO] and Tom is connected to Ana [d’Auchamp, COO] and Terri [MacDonald Riedle, Chief Development Officer] and then the team all started falling into place.

What was important was that they didn’t just see me, they saw the GEIC as well behind me. I said we have the best scientific brains in the 2D materials world behind me, and others don’t have that. They might have one graphene scientist maybe, but we are an army – not just GEIC, it’s the whole graphene ecosystem, with the NGI, institutes and schools in the Faculty of Science and Engineering, turning out highly skilled people.

When I’m looking to hire good people, it makes it easy. Some of them I’ve worked with for six or seven years at the University. I know their capabilities and personality.

What roles do you need to fill to get this thing moving at speed?

Two teams: a materials team, and a scaling and automation team. In automation there are lots of areas: electrical, mechanical, programming, so this would be a 4-5 person team. In materials, the first person is a polymer scientist but we also want somebody in metals, somebody with battery knowledge, solar, so that team also will have people from different backgrounds.

I had supply chain knowledge before and I’ve been working on getting the best supply chain in Manchester: the best machining company, the best electrical cabinet makers, the best automation systems suppliers. I have a good ecosystem of suppliers that will put us in a unique position to take this forward rapidly.

We can claim direct jobs being created but there are also indirect jobs in the supply chain that we contribute to if we are bringing investment into Greater Manchester.

Finally, what do you like doing away from graphene innovation?

I don’t spend much time away from the lab! I like cooking and I like going to the gym but first with coronavirus and now everything on with GIM, I’ve got out of the habit. But my life is work. And when I make a robot I don’t feel like I’m working. I’m having fun!

Vivek will be showcasing his Graphene Space Habitat technology at JEC World in Paris from 3-5 May. Find out more about Graphene@Manchester on our website.

2D MaterialsAdvanced materialsapplicationsgrapheneinnovationinventionManchesterrecyclingrubberspacesustainabilityThe University of Manchester