Guest post: Botany at Manchester – the Secret (and Forgotten) History of Plant Science at the Firs and Jodrell Bank

Social responsibility UOM life 29th July 2025

This blog was written by Rory Baker – student on placement for an MA in the history of science, technology and medicine

Guest post: Botany at Manchester – the Secret (and Forgotten) History of Plant Science at the Firs and Jodrell Bank

Building upon a recent series of blog posts on the impressive history of the Firs Botanical Grounds through its associations with Joseph Whitworth and contributions to the First World War effort, I wanted to further share the often-overlooked legacy of the site through the wider story of botany at The University of Manchester and shed light on the often-overlooked horticultural grounds at Jodrell Bank.

Botany at Manchester: A Very Brief Introduction

Botany at Manchester is as old as the University itself. When Owens college was founded in 1851, William Crawford Williamson was appointed professor of natural history, anatomy and physiology. By 1879, he became Manchester’s first Professor of Botany, focusing his teaching solely on the plant sciences and laying the groundwork for what would become a globally significant department.

Botany at Manchester contributed to both World War efforts, global plant research and national food security. These impressive contributions can be found in the Firs archives on the site itself, tucked away behind university accommodation in Fallowfield. The Firs acts as a remnant of plant sciences at the University after the Botany department was disbanded following a reorganisation of biological sciences in 1986 – a BSc in Plant Science was offered at the University of Manchester until very recently, as the final student graduates in 2026. The Firs thrives today, but much of its remarkable legacy remains to be made public.

For more comprehensive information on the history of botany at the University of Manchester, visit this new timeline.

Cryptogamic Botany under W.H. Lang: from a House of Moss to the Skies

One of the lesser-known branches of botany is Cryptogamic botany, the study of non-flowering, spore producing plants named cryptograms, such as mosses, liverworts and ferns. William Henry Lang, Manchester’s chair of cryptogamic botany from 1909-40, was a pioneer in this field.

Lang authored one of the earliest known publications associated with the Firs: a 1923 paper on the genetic reproduction of Hart’s tongue fern (Scolopendrium vulgare). The research was based on material from Ireland grown in the old Moss House originally located on the Ashburne estate, Fallowfield, and later moved to the Firs in 1922. The Moss house is still used today, standing as one of the oldest functioning facilities on the Firs grounds, home to an array of cryptogams in a perpetually moist atmosphere.

Inside the Moss House at Firs Botanical Gardens – Harts Tongue fern (Asplenium scolopendrium) can be seen on the left

Moss

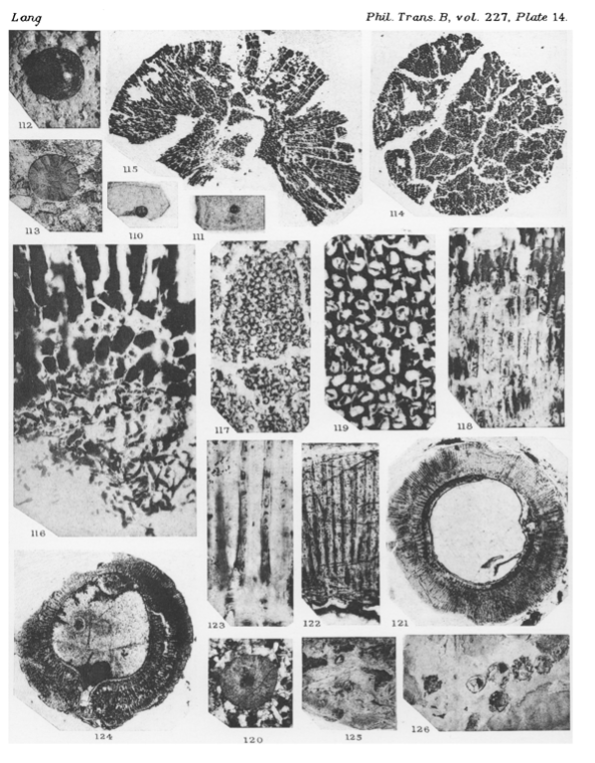

Lang is perhaps best remembered for his groundbreaking palaeobotanical work on fossils of vascular land plants from the Devonian period (419-358 million years ago), especially his 1937 paper “On the plant-remains from the Downtonian of England and Wales”. Lang described unknown fossil organisms that revolutionised our understanding of the genetics and evolution of terrestrial ecosystems. This has furthered our understanding of how plants interact with key earth systems such as the geochemical carbon cycle.

John Walton, a British botanist, argued Lang’s creation of a new taxonomical order – Psilophytales – was the most important contribution of the century to our knowledge of early plant life.

But Lang’s contributions weren’t limited to plants. During the First World War, he worked with Wilfrid Robinson on developing varnishes to protect wood from water damage. Their work reached the Aeronautical Research Committee’s report on wartime aircraft construction in 1920, furthering University of Manchester’s historic contribution to the War effort. Their work tested the tensile strength of ashes, spruce and birch, all of which were used in the construction of De Havilland’s Mosquito, a wooden plane used in the Second World War.

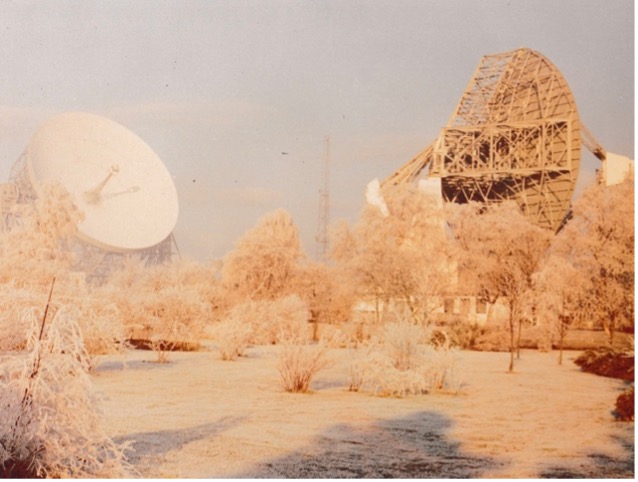

Jodrell Bank – More than a Telescope

Jodrell bank in Cheshire is renowned for the giant James Lovell radio telescope and its astrophysics research, but what is often forgotten is that it also hosted experimental botanical and horticultural research for decades.

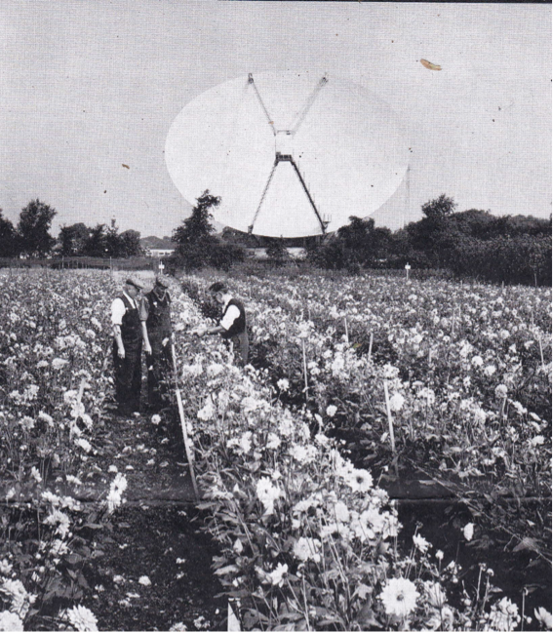

In 1930 a generous donation from the Royal Horticultural and Botanical Society of Manchester allowed JMF Drummond, chair of Botany from 1930-46, to establish experimental grounds at Jodrell Bank, Cheshire. The grounds have conducted a myriad of horticultural, agricultural and zoological experiments (the grounds have been used for experimental work on snails and insects, and at one point, crocodile eggs!). There were close links between the Jodrell Bank site and the Firs, with employees working across both sites.

During WWII, the Jodrell grounds were used to breed hardier, pest-resistant crops to help support Britain’s wartime food security. By 1940, nine acres at Jodrell bank were used to grow produce such as the haricot sans parchemin, beans with an edible pods and seeds with longer shelf lives, onions that can be harvested out of season, and genetically modified cabbages, treated with colchicine, a medication typically used to treat gout, in order to increase their size. The research was not only cutting edge but practical, supporting food production when Britain’s supply chains were under threat.

A Global Botanical Network

Botany at Manchester also played a key role in uniting the international botanical community.

David Henrique Valentine, head of the department at Manchester from 1966-87, was deeply involved with work at Jodrell and the Firs. Valentine was one of six members of the editorial committee for the Flora Europea project, a pioneering 5 volume encyclopaedia of European plants that provided comprehensive information on subspecies, genetics and habitat preference, published in the years 1964-93. This was a huge job, and it stimulated taxonomists and botanists across Europe to serve a shared objective and collaborate, leading to regional offshoots such as Flora Iberica and Flora Hellenica. As such, botany at Manchester and Jodrell bank had helped invigorate taxonomy and plant sciences across Europe.

Seed lists

In 1973, Valentine also expanded the University’s international seed exchange, distributing 217 lists to institutions in 38 countries, from the USSR to New Zealand. This exchange of plant and seed material allows botanical gardens to create a network of plant materials and information for conservation, research and the expansion of collections. Seed exchanges like these allow botanical gardens to grow diverse collections, conserve rare species, and study how plants have adapted to changing climates.

Botany in Decline?

Despite its legacy, Manchester is no longer accepting standalone BSc plant science students, mirroring a wider national decline across British higher education. Between 2007 and 2019, just one student in the UK graduated in the botanical sciences for every 185 students from the other bioscience disciplines. This prompts concerns that British students, and the public more generally, are ill equipped to understand the importance of plant science in helping mitigate environmental change.

Botanical work at Jodrell bank faded in the decade following the closure of UoM’s Botany department. Its focus, as we know, is mainly on astrophysics, although some agroforestry research and landscape and design teaching carried on into the 1990s.

The Firs Today

Thanks to a substantial investment from the University’s Botanical endowment funds, the Firs site was transformed with a new state-of-the-art research greenhouse facility, and with support from the National Environmental Research Council it is now how to the Manchester Air Quality Supersite, opening in 2020. The site supports a broad range of environmental research, with research projects covering ecology, crop sciences, atmospheric sciences, geography, engineering, history, poetry and more.

The Firs is home to student societies and action groups such as the University Botany Society and Manchester Food Partners. It supports the Green Wellbeing Project, providing a safe space for students to connect with nature and plants in its tranquil grounds, and holds regular open days for the public. It continues to host important research, today supporting a strong environmental, ecological and plant research community, helping to work on the many of the pressing problems of our age including crop tolerance, climate change, biodiversity loss, soil health and air pollution, honouring its remarkable legacy.

Earlier this year, researchers began a fungal monitoring experiment at the Jodrell Bank experimental site; and discussions are ongoing about transforming the Firs into a University Botanical Garden, a space for public education, leisure and scientific research, where we can reengage with the importance of nature, our environment and the world of life-sustaining plants.