Turing’s lost letters found in storeroom tidy up

Heritage 25th August 2017

We all have it – that cupboard, cabinet or even room where we ‘tidy stuff away’ simply so we can forget about it. Who doesn’t have a box left unpacked after every home move that they just shove unopened under the bed?

At The University of Manchester, we have our fair share of chocker storage spaces – which is hardly a surprise given the amount of research and work that’s been conducted here over the decades. But when Professor Jim Miles of the School of Computer Science decided to sort out one of the storerooms, there’s no way he could have predicted uncovering a stash of lost letters by one of our most famous alumni.

“That can’t be what I think it is”

As he sorted through one filing cabinet, Prof Miles noticed an orange paper file labelled ‘Alan Turing’ right at the back of the bottom drawer. He tells us: “When I first found it I initially thought, ‘that can’t be what I think it is’”, but inside the folder was a previously undiscovered cache of letters and papers written by the ‘Father of Computing’ himself.

“I was astonished such a thing had remained hidden out of sight for so long. No one who now works in the School or at the University knew they even existed. It really was an exciting find and it is a mystery as to why they had been filed away,” Prof Miles adds.

An enigma

You could say that it’s something of an enigma as to how such a Turing treasure-trove remained undiscovered for so long. The University’s Archivist James Peters notes that archive material relating to Turing is “extremely scarce”, making this a “truly unique find”.

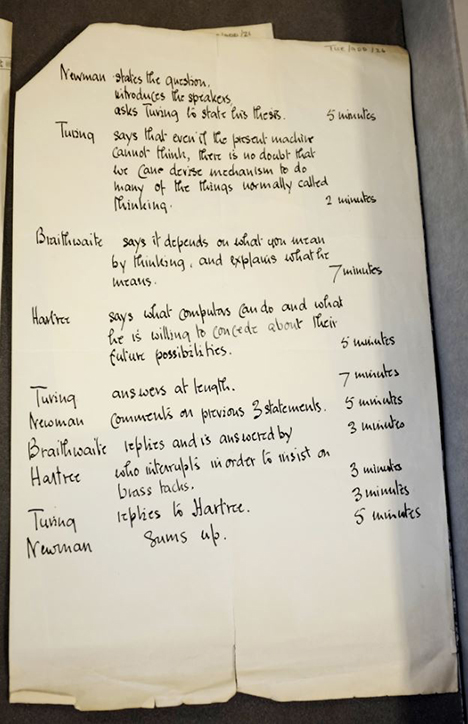

In total, there are 148 documents, which include Turing’s handwritten draft of a programme on Artificial Intelligence (AI) for BBC radio (pictured below), as well as a letter from GCHQ (formerly GCCS) – where he was working when he cracked Germany’s Enigma machine during WWII.

|

|

|---|

Checkmate

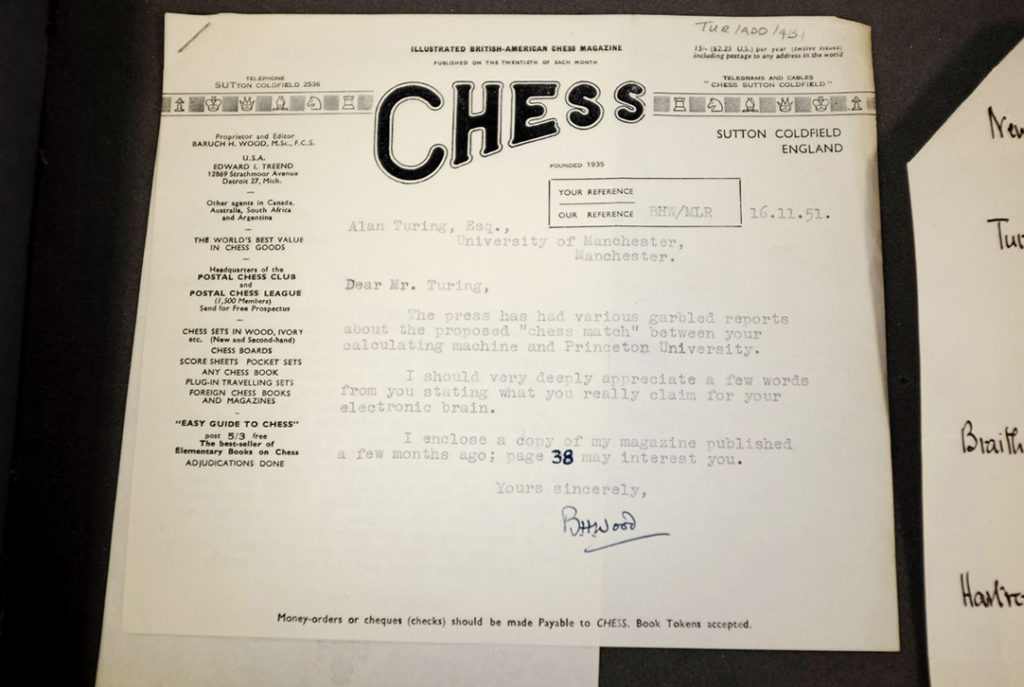

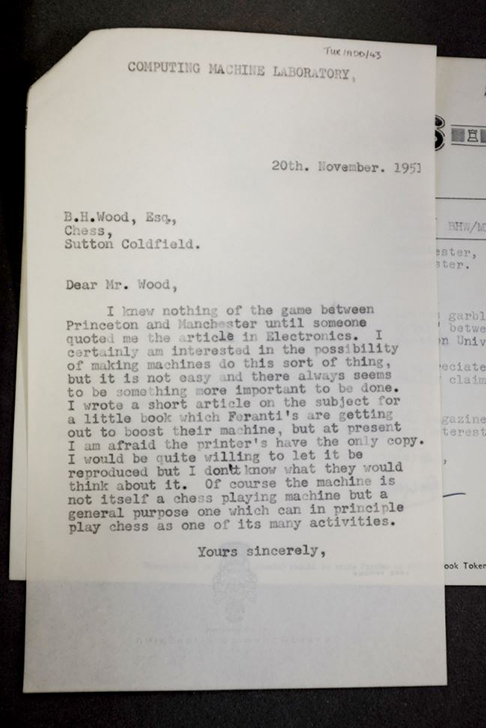

One of Turing’s many accomplishments was to write an algorithm that would allow a computer to play a game of chess against a human. The program – known as Turochamp – obeyed the legal moves of the game and was able to think two steps ahead. While at the University, Turing had started the work that would allow the Ferranti Mark 1 computer to run the program, but never completed it.

His developments in this area were of great interest to both other academics and the press. Pictured above is a written enquiry from someone at a chess magazine into Turing’s chess-playing “calculating machine”. “I certainly am interested in the possibility of making machines do this sort of thing, but it is not easy and there always seems to be something more important to be done,” Turing replied. It wouldn’t be until much later that Turochamp ran on a computer – and it’s amazing to think Turing wrote the algorithm without even having a computer.

The letters also include Turing’s rejection of an offer to attend a conference in the US in the spring of 1953, with the response: “I would not like the journey, and I detest America.”

The letters, which have now been safely catalogued and stored, detail the work and research that Turing was conducting while working at the University. In particular, the find provides an insight into his work in AI, maths and computing.

Scientist, mathematician, inventor and war hero

Alan Turing is among our most celebrated alumni – and with very good reason. He is widely regarded as the ‘father of modern computer science’, and came up with the idea of a ‘Universal Machine’ that could read, decode, memorise and follow instructions. These ideas would ultimately lead to the computers we use today.

Turing was a scientist and mathematician, and his early work on ciphers meant he was snapped up by the British intelligence services to work on cracking the German Enigma machines. These cipher machines were able to encipher signals that could otherwise provide important clues about Germany’s military plans.

Working with other code breakers at Bletchley Park, Turing developed ‘The Bombe’, which was able to break the Enigma codes. It is estimated that cracking intercepted codes helped to end the War earlier than would have otherwise been the case, saving millions of lives in the process.

It ‘s estimated that cracking intercepted codes helped to end the War earlier than would have otherwise been the case, saving millions of lives in the process.

So there’s very little denying that Turing was a national hero. However, during his lifetime he was treated in a far from heroic way. In 1952, while living in Manchester, Turing was arrested and charged for committing gross indecency after revealing to police he was in a sexual relationship with another man.

At this time, male homosexual activity was illegal – and it would remain so until 1967. On the advice of his solicitor, Turing pled guilty to the charge and was given the option of imprisonment or probation – the latter option conditional upon him undergoing hormone treatment akin to chemical castration.

Just over two years after his arrest, Turing was found dead. He had died of cyanide poisoning and his passing was officially ruled a suicide.

Ahead of Manchester Pride tomorrow, we’re proud to celebrate Alan Turing and the wealth of achievements he made during his lifetime. And remember – you never know when tidying up those boxes could really pay off!

Watch our interview with Prof Miles and Archivist James Peters.