Jurassic Park meets Arachnophobia

Departments Research impact and institutes Robotics and AI 14th February 2018

It’s the ultimate 90s movie mash-up – Arachnophobia meets Jurassic Park. And it’s happened in real life, right here at the University of Manchester.

Imprisoned within a block of amber dating back to the Cretaceous period, a spider has been discovered that could provide an unparalleled insight into the evolution of everyone’s favourite creepy-crawly. And to make the discovery even more exciting, this spider had a tail (because having eight legs and eyes isn’t already nightmarish enough).

Does whatever a spider can

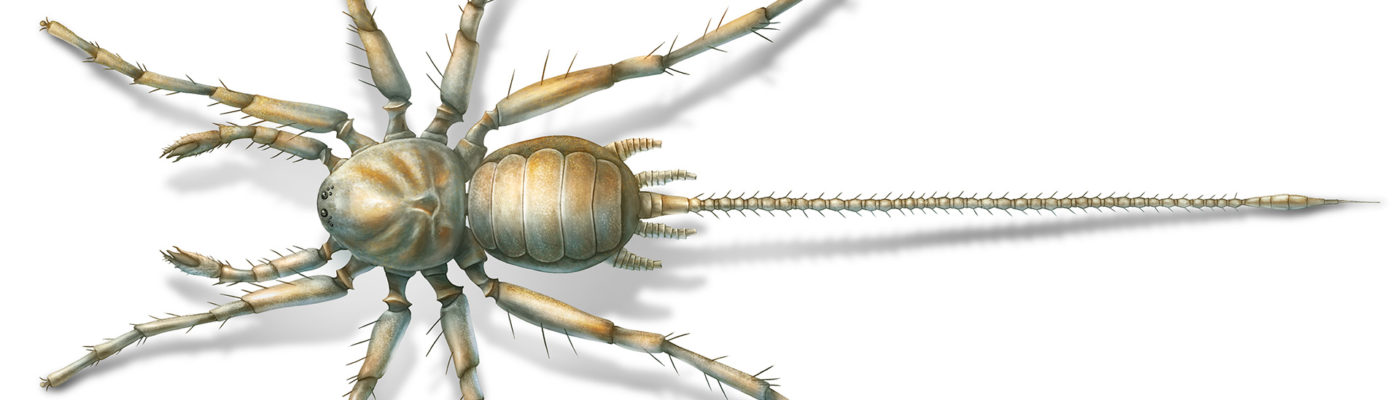

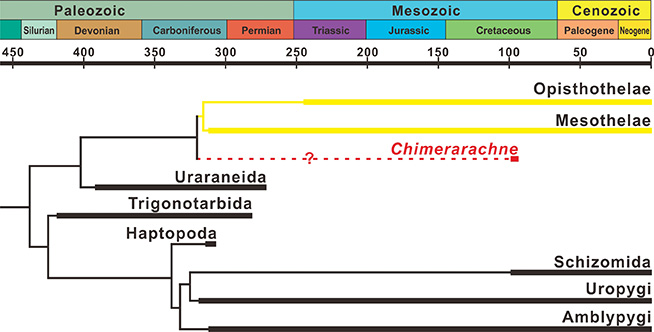

An international team of researchers including Russell Garwood from the School of Earth and Environmental Science here at the University of Manchester have been closely studying a fossil originating from Myanmar that’s an incredible 100 million years old. They conclude the insect trapped within the amber is a previously undiscovered species, which they’ve named Chimerarachne yingi. The ancient beastie is very similar to the most primitive group of spiders to exist today: the mesotheles.

The findings, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, suggest that while the spider is not a direct ancestor of modern-day spiders, it is a sort of ‘missing link’ between ancient arachnids that are long extinct and the little blighter you spotted in the shower this morning. But of course, the spiders weaving webs in your home don’t have tails.

Interestingly, the researchers remain unsure as to what that tail was used for, but believe it is a leftover from earlier incarnations. While spiders today don’t have tails, another modern-day arachnid, the scorpion, does.

Scorpions are also venomous, as are many species of spider, but the researchers are unable to conclude whether Chimerarachne yingi had a poisonous bite.

Web slinger

Co-author Dr Jason Dunlop from Museum Für Naturkunde in Berlin explains that the spider’s body type is unique among arachnids. The discovery therefore poses questions not only about what early spiders looked like, but also how key features unique to this group – like the spinnerets used for spinning and the pedipalp organ – developed. A spider’s pedipalp is a set of appendages that function as a mouth and also help transfer sperm during mating.

Dr Garwood notes that, whereas today’s mesotheles spiders have four pairs of spinnerets, all of which are located in the underside of their abdomen, the fossil has just two pairs of fully developed spinnerets. These are placed towards the back of the spider, while there are two others in formation.

Spiders use spinnerets to spin silk. The organs are highly complex and can move independently of each other, which means spiders can produce different types and strengths of silk for different purposes. Just something to remember when you carelessly walk through a spider’s web or dust one from the corner of your ceiling – a lot of work went into that!

Land before time

“Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the new fossils is the fact that more than 200 million years after spiders originated, close relatives – quite unlike the arachnids alive today – were still living alongside true spiders,” says Dr Garwood.

It’s something to think about before you power up that time machine you’ve been working on. Head back to the Cretaceous period and not only will you have Tyrannosaurus rex and velociraptors* to look out for, but also these crazy betailed spiders.

But wait! The Chimerarachne yingi fossil was found preserved in amber, just like that from which the mosquito blood is extracted in Jurassic Park. So, once again we find ourselves asking, could Jurassic Park happen? If our new spider buddy was to have bitten a Triceratops, could we finally bring everyone’s favourite dinosaur back to life?

Again, we’re afraid to say the answer is ‘no’. And as you know, bursting the Jurassic Park bubble is something of a speciality of ours. First we told you that T-rex couldn’t run, so Jeff Goldblum didn’t have to get into quite such a tiz on the back of that Jeep. And then we revealed that the 2007 discovery of 80 million-year-old collagen preserved in a dinosaur skeleton was in fact a contamination.

Tomorrow’s spiders

But perhaps we should stop obsessing over bringing the past back to life and instead turn our attention to future spiders – or, more specifically, future ROBOT spiders.

Dr Mostafa Nabawy, Microsystems Research Theme Leader at the School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, will give a talk at the forthcoming Industry 4.0 Summit (February 28th to March 1st) about how a jumping spider robot will transform future manufacturing. There’s no word yet on whether these spider-bots have tails – but we’ll be sure to keep you posted.

*You wouldn’t have to worry too much about running into a velociraptor – they were only about the size of a modern-day turkey and were covered in feathers. Wrong again Jurassic Park!

dinosaurDinosaursEarth and Environmental SciencesfossilJurassic ParkSEESspider