Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell – our science superstar

Departments Heritage 11th February 2019

Today (11th February) is the United Nations’ Day of Women and Girls in Science – a day to recognise the women making strides in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

It’s also a day dedicated to recognising the very real gender gap that still exists in these fields, where women are significantly underrepresented.

For example, did you know that since it was launched in 1901, the Nobel Prize has been awarded to just 51 women? That’s out of a total of 590 winners – meaning women make up just 8% of the overall prize winners.

And it’s not just at the very top where women are underrepresented in STEM. From the classroom to the lab, there’s a shortfall of women in these disciplines. In fact, the Institute of Physics previously noted that only one in five students who sits an A-level in physics is female.

Yet some of the very brightest stars in physics are women – and Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell is among the brightest.

More than a blip

It’s 1967 and a group of physicists are tirelessly assessing miles of paper printouts from a chart recorder busy tracking the stars. Among them is Jocelyn Bell, who was attending New Hall College at Cambridge University to study towards her PhD in physics.

While staring at the reams of paper, Dame Jocelyn noticed something – a bit of “scruff” on the paper. Going back over the paperwork, she realised that the pulse repeated itself. It was unusual and unexpected, and so the signal was nicknamed the “little Green Man”.

“It was a very, very small signal,” Dame Jocelyn told the Guardian of her discovery, which was akin to finding a needle in a haystack – actually, it was more like finding a grain of rice in the Sahara Desert. Indeed, Bell noted that the signal “occupied about one part in 100,000 of the three miles of chart data that I had”.

Though it appeared as just a blip on the printout, what Dame Jocelyn, who is an honorary graduate of The University of Manchester, had discovered is one of the most spectacular phenomena in all the cosmos – the pulsar.

Making waves

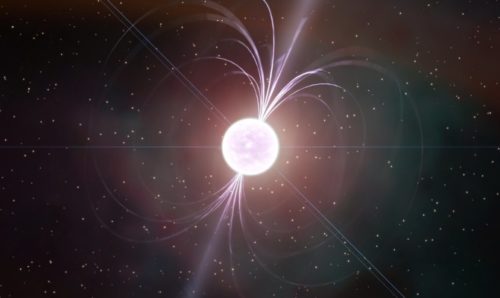

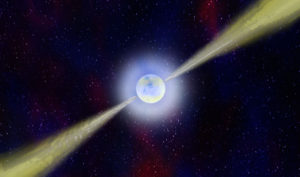

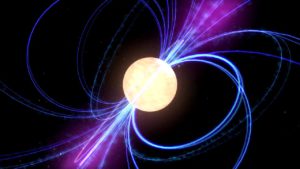

When a giant star dies, it rapidly collapses in on itself to form an incredibly dense but tiny body known as a neutron star. As it collapses, the neutron star rotates rapidly – sometimes as fast as a few hundred times a second.

Some of these neutron stars shoot out beams of electromagnetic radiation from their poles. Because these beams can only be seen from Earth when they are pointing in its direction, they appear to pulse – and so they were named accordingly.

Pulsars are very helpful to astronomers as they can use them to gather information and even conduct experiments. Indeed, gravitational radiation was confirmed to exist after scientists witnessed the impact of gravitational waves on a pulsar’s pulsing.

A prize omission

There are few who would argue that Dame Jocelyn’s discovery was one of the most important of our time – and it’s little surprise that the work led to a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974. And yet Dame Jocelyn was not named on the award and received no official recognition for being the astronomer who made the discovery. This is in spite of the fact she waited some time to verify and share her observations, and then needed to argue successfully that the radio waves were coming from many lightyears away, and were not simply caused by interferences here on Earth.

Despite the omission, Dame Jocelyn has never complained. However, she told the BBC: “There certainly has been a notable lack of women Nobel Prize winners, except maybe in areas like literature where you know there are women.” She added: “I think in part that’s to do with the age profile of the women that there are in the subject at the moment. Nobel Prizes rarely go to young people; they more often go to established people and it’s at that level that there are fewer women in physics.”

While she missed out on the Nobel Prize, Dame Jocelyn’s career has not been short of accolades, such as the Breakthrough prize she picked up in 2018. Also last year, The University of Manchester named the lecture theatre in its new annex of the Schuster Building in her honour.

Fear of failure

There’s certainly still work to be done to encourage more women to follow in Dame Jocelyn’s footsteps. She was only 24 years old when she discovered pulsars, and yet the dropout of girls from STEM subjects occurs at age nine and ten. A major reason for this is the tendency of girls to struggle with confidence, which means they fear failure – and failure comes part and parcel with succeeding in science.

Fear of failure was something Dame Jocelyn used to push herself, telling the Guardian: “I noticed [the signal] because I was being really careful, really thorough, because of impostor syndrome.” And she told the BBC: “I found pulsars because I was a minority person and feeling a bit overawed at Cambridge. I was both female but also from the north-west of the country and I think everybody else around me was southern English.” Dame Jocelyn donated the £2.3 million fund she received from the Breakthrough prize to help under-represented groups study physics.

There’s no better time than UN Day of Women and Girls in Science to remind you that you are not an impostor – and there is no such thing as failure in science. After all, even a blip could turn out to be the most important astronomical discovery of a generation.

Words – Hayley Cox

Images – Tatiana T, The University of Manchester, Jodrell Bank

astronomyDame Jocelyn BellheritagePhysics and AstronomypulsarsSpace