Guest post: The Firs’ World War – medical botany from Fallowfield to the frontline

Heritage Social responsibility UOM life 30th March 2023

Henry Lloyd-Hughes, a Manchester student conducting work on the fascinating archive of the Firs Environmental Research Station, digs a little deeper into the facility’s important – and surprising – contributions to the First World War…

Following a post on the Firs’ fascinating history in 2020, I wanted to take a closer look at a particularly interesting aspect of the site’s story: its contributions to the First World War effort.

The Firs Environmental Research Station, tucked away on Fallowfield Campus, remains a largely overlooked part of the University’s past and present operations. Today, the Firs is a centre of cutting-edge research into climate change and food security, hosting a new fully climate-controllable, state-of-the-art, £2 million greenhouse.

Its living plant collection is also highly impressive, containing a wide diversity of tropical, sub-tropical, drought-tolerant, Mediterranean and alpine species, with native environments ranging from Southeast Asia to the Amazon, Southern Africa and the Canary Isles, as well as a collection of rare ferns and mosses.

However, as I have found while working on placement in the Firs’ archives, there is a longer legacy of important botanical work to be uncovered here, which marks an important part of the University’s broader history.

A brief history of the Firs

We can trace the history of the Firs back to December 1853, when Joseph Whitworth, famed engineer, entrepreneur and philanthropist, bought the land in Fallowfield where the site sits today.

In 1854, at the request of the government, the War Office built a shooting range where temperature-controlled greenhouses now stand (still referred to as ‘The Range’). It was here that the famous Whitworth Rifle was tested and developed – considered to be the most accurate percussion rifle of its time.

In 1881, Whitworth relocated from his Fallowfield estate and leased its house and gardens to his friend Charles Prestwich Scott, who was the first editor of the Manchester Guardian. Ultimately, both the house and its lands were then passed into the ownership of the University, where it would serve as the official residence of the Vice-Chancellor until the 1990s.

Medical botany and WWI

In 1914, with the onset of the First World War, Britain was facing a huge crisis in terms of the supply and production of vital antiseptic and plant-derived drugs, which were widely needed for both military and civilian use.

At this time, Germany controlled up to 80% of global pharmaceutical production and, along with its allies, the major supply of raw plant materials from which crucial drugs were derived.

This crisis led to countrywide calls in Britain for the domestic cultivation of medicinal plants, which included belladonna (Atropa belladonna), henbane (Hyoscyamus niger), thorn apple (Datura stramonium), autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale), foxglove (Digitalis) and valerian (Valeriana officinalis), which was coordinated by the National Herb Growing Association from January 1916.

By 1917, thanks to the collective initiative of the British Government, drug companies, academic botanists, university researchers, commercial producers and amateur growers, enough raw plant material was collected to meet national needs and largely avoid further drug crises.

The Firs’ medicinal plants

According to records, the first botanical grounds at the site were established in 1907, behind Ashburne Hall, which today remains a popular undergraduate and postgraduate hall of residence on Fallowfield Campus. They moved to their current location under the direction of F E Weiss, who served as the George Harrison Professor of Botany from 1891 and remained its Chair until 1930.

The Firs was actively engaged in helping the national war effort in terms of plant production, as is reflected in the University Council Minutes from 1915:

“War Effort – Owing to the scarcity of the drugs obtained from Belladonna (Atropa belladonna), and Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger), The Oaks [Oak House area, which backs onto the Firs] have been used for the cultivation of these important medicinal plants.”

Both of these plants were hugely important during wartime owing to their medicinal uses.

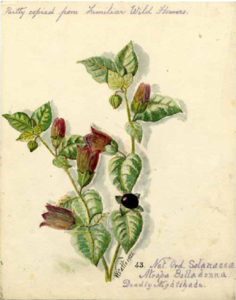

^Deadly Nightshade (Atropa Belladonna). William Catto,1921, watercolour on paper.

Belladonna, more commonly referred to as ‘deadly nightshade’, contains the alkaloid atropine, which can be extracted from the plant and has various medicinal applications. Most notably in the context of WWI was its use as an antidote to nerve gas poisoning, which became much more prevalent with trench warfare.

Atropine is also extremely useful for eye operations, for it is known to dilute the pupils and make surgery easier, something which was unfortunately also more commonplace as a result of the development and use of mustard gas. More generally, liniments of belladonna were used to relieve soldiers’ muscular aches and strains.

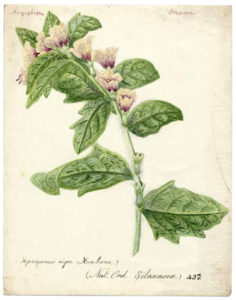

^Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger). William Catto, 1904, watercolour on paper.

Henbane is also of the nightshade family, and produces the toxin hyoscyamine, from which the drug hyoscine was made. Also known as ‘Devil’s Breath’, hyoscine is a tropane alkaloid used to relieve motion sickness and postoperative nausea.

This drug was especially useful during the First World War in helping soldiers who suffered from seasickness. Hyoscine was also widely used as a relaxant and pain killer throughout the war, and importantly was administered as a tranquiliser for shellshock.

Putting the Firs first

The Firs’ medicinal contributions during WWI mark just one element of the site’s long and significant history.

By bringing attention to the Firs, I hope to raise awareness of both its former and future importance as the University’s main centre for botanical research.

It may be hidden away in Fallowfield, but between the part it played in helping produce vital plant-derived drugs during WWI and the instrumental work it undertakes on a daily basis, it’s high time the Firs got some of the recognition it deserves.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with the latest posts from The Hub.

Words: Henry Lloyd-Hughes

Images: Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums (Creative Commons), Shutterstock

Earth and Environmental Sciences

penny Griffiths says

Very interesting.

On Dartmoor many women collected spangham moss which were used as field dressings during world war 1 very succesfully.

Ros Tratt says

A very interesting read! Some important drugs are still extracted from plants rather than being synthesised in a lab. It’s good to remember how important plants are in medicine.