Sound of the Underground: making music from particle physics

Welcome to Physics 18th December 2020

Earlier this year, composer Nora Marazaite debuted a piece of original music with an unusual inspiration – it was based on the PhD research of one of her old school friends, particle physicist Gediminas Sarpis. They had both moved from Lithuania to Glasgow for their undergrad studies, Gediminas completing an MSci in Theoretical Physics at Glasgow University and Nora studying composition at the Royal Conservatory of Scotland.

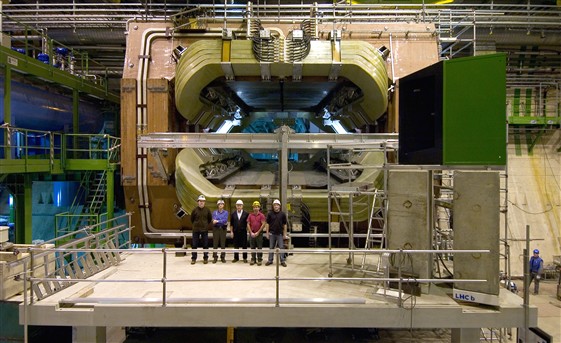

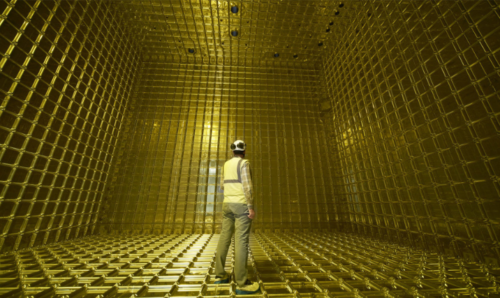

After graduation, Gediminas joined us here at Manchester for his PhD. He was part of the LHCb research group – particle physicists working on the Large Hadron Collider beauty experiment at CERN in Geneva. It was while writing up his thesis on asymmetry that he revisited Glasgow and caught up with Nora. After a long discussion on his research and music theory, she proposed writing a full composition based on his research. She ended up creating a piece scored for a trio of saxophones, an electric guitar, and two percussionists playing a whole suite of instruments from a bass drum and bongos to a giant metal sheet and children’s ‘tinkle toys’.

What was it like hearing his thesis turned into music? Gediminas told us: “It is truly surreal. We can describe scientific theories using maths. However, sometimes it is hard to enjoy maths or “jam” with maths. Music is much closer to the subjective experience of being a person, a consciousness observing the external and the internal cosmos. Listening to “My PhD thesis”, as I jokingly call it, gives me goosebumps.”

Nora said, “I am fascinated by the opportunities offered by interplay between music and science – since High Energy Music I have already collaborated with a Glasgow University PhD Engineering student on a string orchestra piece based on a specific ultrasound device, Switch, premiered in Lithuania this August. I am excited to continue to explore what these interdisciplinary collaborations can offer.”

You can hear the full impressive performance below, and scroll down for the rest of our interview with the composer and her physicist collaborator.

Interview

Where did the original idea for this collaboration come from, and how long did you work together on it?

Gediminas: “Nora and I met more than a decade ago in Lithuania, we went to the same high-school! By chance, we also moved to Glasgow to study. I graduated from Glasgow University with an MSci Theoretical Physics degree. Nora studied composition in the Royal Conservatory of Scotland. During the years of studies, we’ve become very close friends. Last year, while writing up my thesis I visited Glasgow. We spent 5 hours talking about my Physics research, as Nora is an avid follower of Sci-Fi, Pop-science. Then we spent another 5 hours talking about music theory. I must admit, my understanding of it is very minimal, but Nora has been giving me private classes. In our discussions we’ve imagined the emergence of the familiar musical ratios and concepts in an alien civilization. We tried to answer the question, “Which parts of music are inevitable?” “What is purely cultural and human?”. Not long after that, Nora approached me with this idea of writing a full composition based on my research. I agreed on the spot.”

Nora: “I got a commission to write a piece for a saxophone trio, electric guitar and two percussionists with a rare opportunity to use Steve Forman’s percussion collection. I have been working on collaborations with non-musical fields for the last year and thought that this particular uniquely balanced ensemble would require unusual solutions; I offered Gediminas an opportunity to collaborate and he agreed. We had a few initial long sessions, discussing various options and approaches; I then set off to work and contacted him with any questions and ideas – we stayed in touch throughout.”

Could you give a basic summary of the research that this piece was based on?

Gediminas: “One of the biggest existential questions of humanity is “Why is there something rather than nothing?” (Usually attributed to Leibnitz). Finally, scientists are inching forwards towards a possible answer. Surprisingly, the answer lies in an asymmetry between matter and its counterpart – antimatter. If the universe was perfectly symmetric, both kinds of matter would cancel out. However, we are here, hence there must be a difference!”

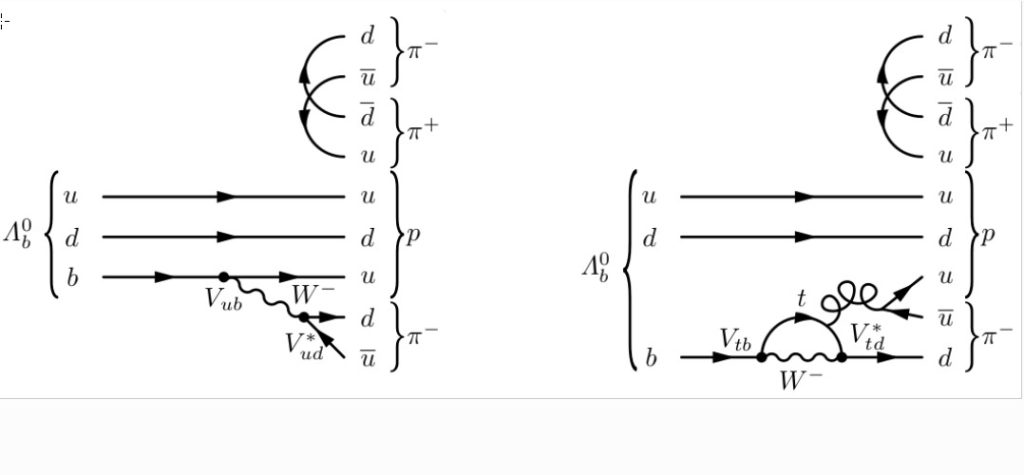

“Physicists call this difference ‘CP violation’ – a mismatch between how particles and antiparticles behave. My PhD topic was a search for this asymmetry in a very specific set of particle decays, where a heavier “cousin” of proton – the Lambda_b baryon – decays into 4 other particles. The particle decays are produced by accelerating protons to almost the speed of light in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Switzerland. These decays are detected by the LHCb detector, which is designed with the CP violation analyses as one of its main purposes.”

Read one of the papers from Gediminas’s research which inspired the performance:

Question for Nora: what was the process like? How to do you turn particle physics research into music?

“Turning any kind of non-audio data into music can very easily become a ‘translation’ trap, where all values are taken literally and with the same level of importance, often resulting in directionless mish-mash of sound (you can hear many examples of this on youtube and elsewhere online). Even in this type of word-for-word translation, where, using software, one can achieve extreme accuracy in expression of values, there is still the problem of multiple parameters being ignored/not included, arbitrary or preferential selection of data to include and systems to apply to achieve a desired audio output. In addition, as soon as one claims to have translated difficult concept X into music, there are immediately other questions: what about the end music product is so special? Is it art or experiment? How scientifically rigid was the process?

“I feel that this is where I, as a composer, come in. My goal is to create a work of art that engages the listener; this approach leads to the search of new forms and structures. The challenge of creating restrictions by limiting the source of data (one can call that inspiration), setting boundaries (employing this data) and trying to achieve musical coherence is what interests me in composition. I have always been interested in the underlying principles of the world around us and I believe these principles offer a future inspiration for new forms, structures and compositional decisions. I fully embrace the fact that there will always be ambiguities and it is important to remember that at the heart of things there is a knowledge barrier between the collaborators (I can never claim to be a competent scientist and vice versa); however, it is also where the interest lies.

“A few concrete examples of approaches taken:

- The sequence of all pitches is pre-decided and strictly followed throughout the piece. I use numerical data (results from paper) as a starting point and use various shifts to generate pitch rows.

- The type of material: in the free section the music is written in a way where synchronous actions can be performed by ensuring eye contact between player pairs (an interpretation of interaction).

- The role of the scientist as both an observer and interferer: the piece begins unconducted, with the conductor only indicating the start of bars. It then moves on to strict, timed and conducted material – there is both a visual (conducting begins) and audio change (different kind of music, more movement).

- Two asymmetrical movements: long and short, signifying the miniscule process itself and its implications (the titles of the movements are Zoom In and Zoom out) in reverse (small size – large movement and vice versa).

And finally: Gediminas, any plans for future collaborations between science and art?

“I am active in many areas of outreach and would definitely consider further collaborations. Finding synergies between science and art is a very good approach to make scientific concepts more approachable for non-scientists.”

Pictures of LHCb are by Maximilien Brice

Leave a Reply