Why it’s time to be frank about nuclear

Our partners 28th June 2017

In order for people to seriously consider nuclear as an alternative to fossil fuels, the industry needs to continue being open, honest and straightforward in its discourse.

That’s the conclusion of ‘Making Sense of Nuclear’, which is released today (June 28th – download it here). The new publication has been produced by Sense About Science with help from The University of Manchester’s Dalton Nuclear Institute, Imperial College London, National Nuclear Laboratory and Energy for Humanity.

Stigma

To tell the truth, there’s a bit of a “stigma” attached to nuclear, as Professor Francis Livens, Director of Dalton Nuclear Institute, acknowledges. “The nuclear sector in the UK is one of the safest and most highly regulated industries in the world. But there is still a stigma attached to it, and that has to change,” he points out.

The thing is, while the nuclear industry was once renowned for its secrecy, a lot’s changed. Today, the sector is very different. But, as the authors of the report admit, it’s this history that has helped to create a certain amount of suspicion about the sector. If public opinion is to change, this sense of openness needs to continue.

After all, there are those who feel nuclear power could be the answer to a low-carbon future. This includes a growing number of environmentalists, who believe that nuclear power could provide affordable energy without the greenhouse gas emissions.

But there remain concerns about nuclear’s long-term effects on health, as well as how it is managed – particularly in light of events like 2011’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, which followed the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. The aim of the Making Sense of Nuclear report is to shed more light on these concerns. It provides details on the long-term safety record of nuclear power production. It also details the latest technological developments that have improved its efficiency and safety.

What is nuclear fission?

Before we go any further, now’s probably a good time to talk about what nuclear power actually is. And it all started here in Manchester!

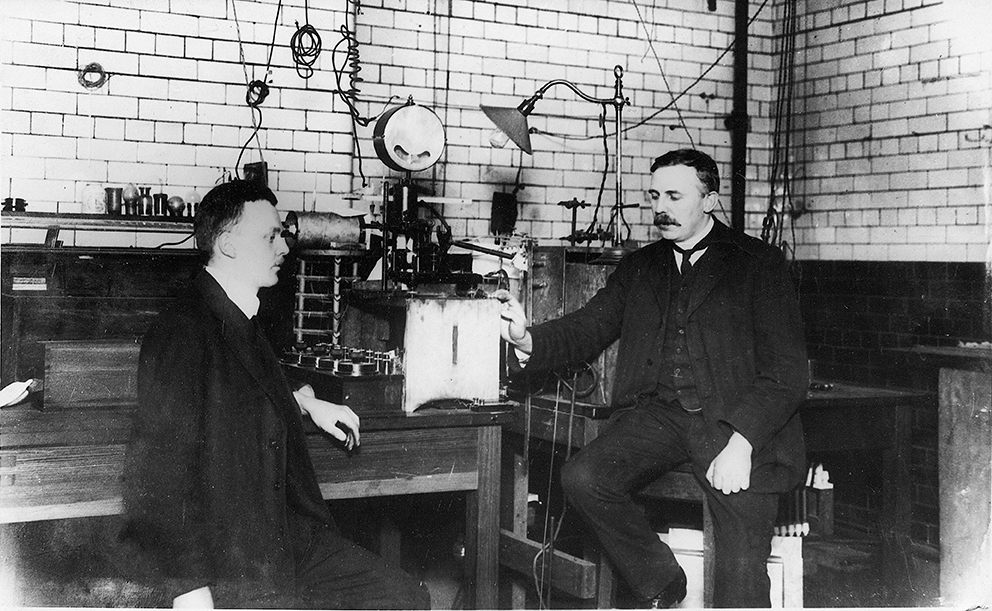

Ernest Rutherford, the Nobel prize winner and former Chair of Physics at the Victoria University of Manchester (now The University of Manchester), is credited with being the first person to split the atom, in addition to numerous other atomic discoveries. Before this, it was widely believed that the atom was the smallest particle in existence, but Rutherford changed all that.

Using the Rutherford-Geiger Detector, which he invented with Hans Geiger, Rutherford demonstrated that rather than an atom containing electrons held within a positive charge, it contained a nucleus made up of protons and neutrons. The majority of an atom’s mass is concentrated within this nucleus, along with its positive charge. Rutherford made this discovery in Manchester – in his lab near Oxford Road.

Thanks to this discovery and his later breakthroughs – which included splitting the atom – Rutherford is widely considered to be the father of nuclear physics. His work is the basis of today’s nuclear power industry.

When an atom is split, it releases a huge amount of energy. This is the basis of nuclear power. In a process known as nuclear fission, an isotope – which is the name given to an atom that has the normal number of protons and a different number of neutrons – is struck by a particle colliding with it at high speed. This causes the atom and its nucleus to split, which releases lots of energy.

Nuclear power reactors use uranium atoms, and the energy released from the fission process heats water and generates electricity. Nuclear fission also produces neutrons, which go on to collide with other atoms, resulting in a chain reaction (watch this video for a good demonstration of how chain reactions work). This chain reaction is controlled carefully within power stations, and the energy produced is safely regulated.

The future of energy

Here are a few facts about nuclear:

- Nuclear fission releases no CO2. None. It doesn’t release any other air pollutants either.

- 1kg of uranium provides enough energy to power a home for 166 years. 1kg of coal would power that same home for just half a day.

- If all the electrical power you ever used – which, if you’re anything like us, is quite a lot – was powered by nuclear, the resulting waste over the course of your lifetime would fit in one drinks can.

It’s figures like this that have made nuclear power a crucial contender in the on-going energy debate.

“We all — researchers, environmental groups, science bodies — have to press for a frank and up-to-date picture of how nuclear reactors and safety systems compare, and their changing costs and benefits,” Prof Livens urges.

But the report’s authors also want to be clear that the aim of the Making Sense of Nuclear initiative is not simply to promote nuclear power. Rather, Director of Sense About Science Tracey Brown explains that it is an up-to-date look at the industry. This is important if nuclear is to be part of the broader debate on energy generation.

Safe as bananas

We can’t talk about nuclear energy without addressing the health and safety impact. For many people, their top concern about a nuclear future is the long-term effect the resulting radiation could have on their health.

Radiation actually exists all around us. It can occur naturally, so it’s been here a lot longer than nuclear power plants. The sun produces radiation, but so do rocks. And while manmade processes like x-rays and flying are sources of radiation, there are natural sources too – like Brazil nuts and even bananas!

Scientists measure radiation in millisieverts (mSv). The radiation dose linked to living near a nuclear power station for a year is just 0.01 mSv – that’s less than taking a single transatlantic flight (0.08 mSv).

There is a limit in place as to how much exposure employees at nuclear plants can have each year (20 mSv). Great care and attention goes in to planning and building nuclear facilities to ensure that workers are safe.

Then there’s the question of waste, and it’s true – nuclear fission does produce nuclear waste. However, this is far less than the amount of harmful carbon dioxide waste the burning of fossil fuels generates. This may explain why so many environmentalists are now looking to nuclear as a serious alternative to coal, oil and gas.

High-level nuclear waste – which is the most radioactive – is converted into glass, which makes it chemically stable. This is currently housed in special storage facilities, but there are plans in place to build a geological disposal facility deep underground in the UK.

So, could the future be nuclear? Well, sharing up-to-date information and maintaining a policy of honesty and openness means it can certainly be part of the debate. As Prof Livens says: “Whether we’re open-minded opponents, reluctant accepters or strong advocates of using nuclear power, we need an open and honest discourse.”

Words – Hayley Cox