Happy birthday, Baby: Tom Kilburn and a new era of computing

Departments Heritage 20th June 2019

This month marks a special birthday – of significance not only to The University of Manchester, but the modern world. This month marks the birthday of the ‘Baby’.

Shortly after 11am on June 21 1948, some 71 years ago, the Small-Scale Experimental Machine successfully executed its first program. It was the first stored-program electronic digital computer on the planet, was nicknamed the Baby and was created right here, at Manchester.

To celebrate we take a closer look at one of the men who built it: Tom Kilburn.

The Kilburn Building

Recently on The Hub we’ve featured various figures after whom the University has named buildings on North Campus – Renold Building and Barnes Wallis, the Ferranti Building, and James Lighthill Building and Morton Laboratory. Such was Kilburn’s impact at the University and beyond that the Kilburn Building, the red-brick, slatted staple of the Oxford Road Corridor, is named after him.

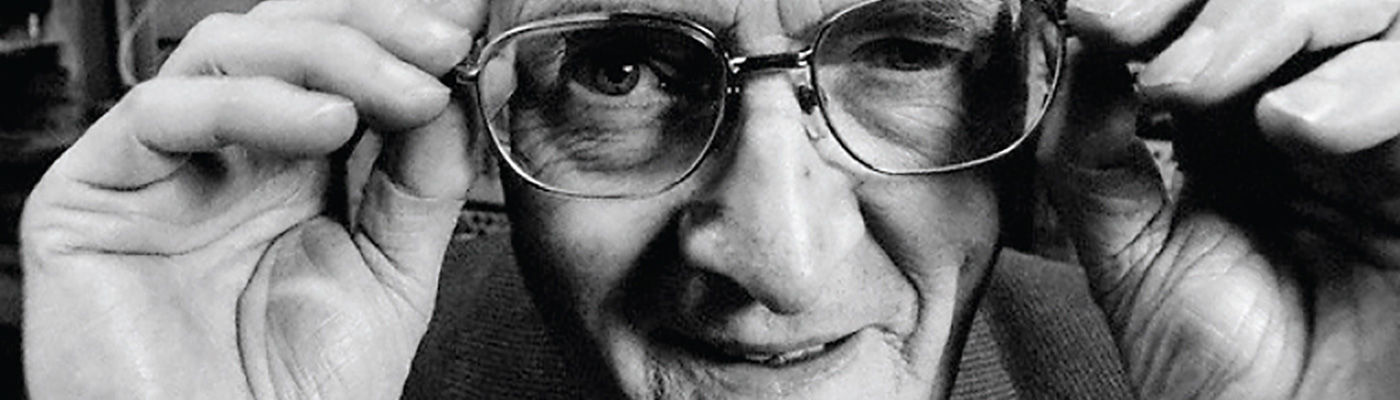

A quiet, polite and unassuming Yorkshireman, Kilburn would play a crucial role in the birth of the computer industry.

After graduating from the University of Cambridge in 1942, where he formed part of the ‘New Pythagoreans’ – a clique with the Cambridge University Mathematical Society – Kilburn was recruited by CP Snow, a physical chemist, novelist and civil servant of some repute (so much that he featured on the Nazi’s Special Search List, a rundown of people to be arrested and handed to the Gestapo should Germany successfully invade Britain), and posted to the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) in Malvern, where he’d work on radar to assist the war effort.

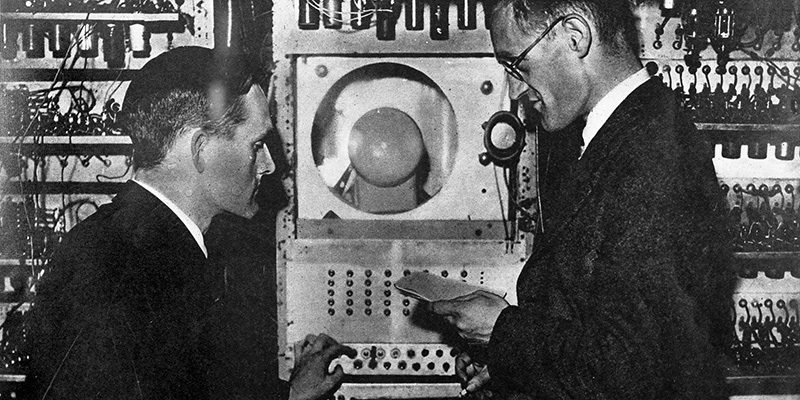

It was here that Kilburn met FC Williams. Together the two would change the face of modern computing; their initial meeting, however, wasn’t quite so buoyant. Kilburn has laughingly recalled how group leader Williams was unable to disguise his disappointment at being presented with Kilburn, a mathematician, rather than a ‘proper’ electronics expert.

The Baby

The frosty reception would soon thaw and the two formed a productive working relationship, leading to the development of the Williams-Kilburn tube – a storage device based on a cathode ray tube – in July 1946. The device would enable their next big creation, the Baby, to store information as electrostatic charges.

Later that year Williams took up the Edward Stocks Massey Chair of Electronics at The University of Manchester – and brought Kilburn with him. Initially coming to Manchester on secondment from Malvern, Kilburn would stay much longer than first anticipated and would play a key role in establishing the University as a world leader in computer design.

This started with the Baby. Built using old supplies from World War II – including from top-secret code breaker location Bletchley Park – and mounted on old racks from the Post Office, the machine stood 16 feet long and weighed half a ton. You’d be forgiven for thinking the Baby a strange name for something so big; however it was tiny in comparison to the ENIAC computer built in the US two years earlier. This was almost 95 feet long, weighed 27 tons and, unlike the Baby, couldn’t store memory.

Williams and Kilburn were joined at Manchester by Geoff Tootill. Another ex-TRE colleague, in his spare time Tootill toured with a troupe called the Flying Rockets Concert Party – comprised of singers, musicians, magicians and more – as well as the Royal Aircraft Establishment Operatic Society and the Savoy Singers, and loved to travel with his family around the UK and Europe in their caravan. In the lab his contribution was invaluable – and two computer clusters in the Kilburn Building bear his name in recognition.

To avoid electric shocks, the team would always keep one hand in their lab coat pocket, never touching equipment with both hands at the same time. Despite struggles to make the machine work, their efforts paid off on June 21 1948 when the computer clicked into action. Not once, not twice, but over and over. They’d done it. The first proper computer program ran by determining the highest factor of a number. An historic achievement with celebrations to match – lunch bought from the canteen instead of homemade sandwiches!

A new era

The Baby would usher in a new computing era, described by some as the birth of software. Kilburn would remain at the forefront (Williams later stated: “I’m not really interested in computers. I made one and I thought one out of one is a good score so I didn’t make any more!”), and a procession of new computers followed. These included the Manchester Mark 1, which was around three times bigger than the Baby; the Ferranti Mark 1, the world’s first commercially available general purpose computer; and the Atlas, one of the first-ever ‘supercomputers’.

An early user of the Manchester Mark 1 was another famous name linked to Bletchley Park: Alan Turing. Arriving at the University in 1948, Turing – widely regarded as the creator of modern computing and known as the man who cracked the Enigma – assisted Kilburn by writing the first version of the computer’s programmer manual, and also acted as a consultant in the development of the Ferranti Mark 1.

Kilburn was not only instrumental in the onset of a new age of computing, but also in steering the direction of computer science and electrical and electronic engineering at the University. After receiving his PhD under the supervision of Williams in 1948 and becoming a professor of computer engineering in the Department of Electrical Engineering in 1960, he would play a key role in forming the School of Computer Science in 1964. He would become the first Head of Department before serving as Dean of the Faculty of Science from 1970 to 1972, and later as Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the University from 1976 to 1979.

A family man… with a love of Manchester United

Kilburn’s links to Manchester didn’t start and end with the University. He was an avid fan of Manchester United and loved to see them play. He described going to see the team lift the European Cup at Wembley in 1968 as one of the best days of his life, and was also thrilled to see the team collect, over 30 years later in 1999, the same trophy along with the Premier League and FA Cup as part of an historic treble.

He and his wife Irene had two children, John and Anne, and the family habitually holidayed in Blackpool during the summer. Partly because there was lots to keep the children entertained, partly because it meant never missing United’s first home game of the season! He was also a fan of music, mainly jazz, and would play the piano from time to time.

Kilburn died aged 79 in January 2001. Just a few years earlier in 1998 he unveiled a fully functional replica of The Baby at Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum. He and Tootill both approved of the machine – but both agreed it was much too clean!

Tom Kilburn: an understated Yorkshireman with a dry sense of humour who helped change the computing landscape. Not bad for someone who never owned a personal computer…

Words: Joe Shervin

Images: Carolyn Djanogly, The University of Manchester, Joe Shervin

Be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with all the latest posts from The Hub.

Computer ScienceElectrical and Electronic Engineeringheritagehistory

Sven Hammarling says

There is a blue plaque for Tom Kilburn at Dewsbury railway station, alongside one for Leslie Fox. They both attended the Wheelwright Grammar School.

https://www.examinerlive.co.uk/news/blue-plaques-unveiled-recognition-two-13361771

Joe Shervin says

And well deserved too! Thanks for the info Sven – really interesting!