Trusting your robot colleagues part one: What is a robot?

Blog 12th July 2022

Author: Ian Tellam, Postgraduate Researcher, School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester

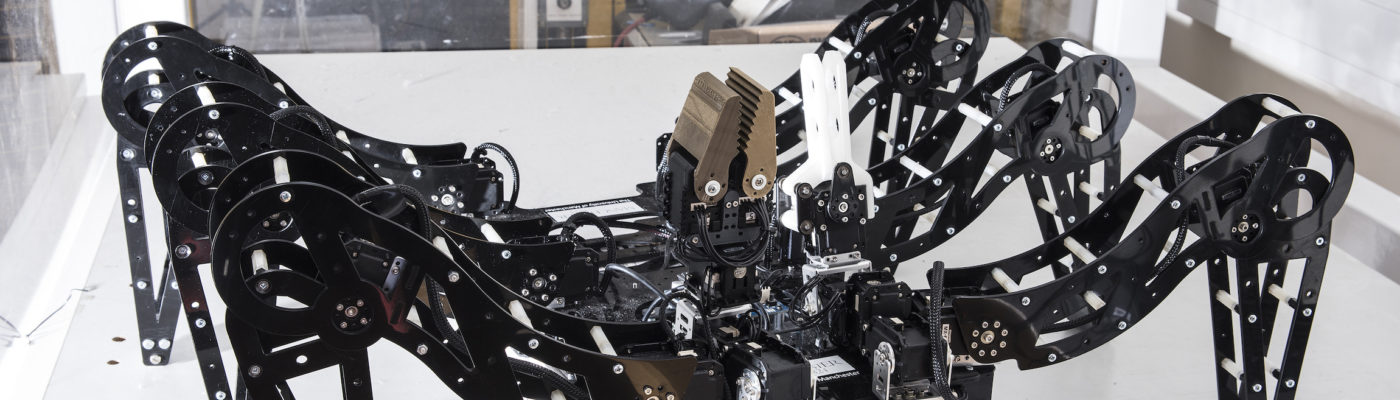

During my research, looking at the introduction of ‘robots’ in nuclear decommissioning raised an interesting and perhaps unanticipated, question. What was I actually looking at? On the face of it the question seemed obvious; most people feel they’ll have an intuitive understanding of what a robot is when they see it. But how do you actually define it?

Turning to the internet, it seems the definition of a robot in the public sphere tends towards a mixture of real-life robotics and the speculations of science fiction. Google tells us a robot is “a machine resembling a human being and able to replicate human movements and functions automatically.” According to Wikipedia “a robot is a machine – especially one programmable by a computer – capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically.”

From an engineering perspective the human resemblance, or even a degree of autonomy, is not a prerequisite to earn the label of ‘robot’. A robot is often considered to be any piece of moving machinery that has some amount of software control. This is an extremely broad view on what a robot might be, potentially encompassing devices like conveyor belts on production lines, which are pretty far from many popular conceptions of robots. It would also exclude the various remote-control devices that are usually termed robots: a bomb-disposal ‘robot’ for instance. Or various remote-controlled devices used in the nuclear industry. Does that mean the definition is wrong, or that the people who term such things as ‘robot’ or ‘non-robot’ are incorrect?

Clearly, when people talk about adopting robotics in their workplace they normally have some sort of idea of what that would look like and the tasks that they might perform. But this concept may not line up exactly with the definition a developer may accept, and expectations of these different parties of the capabilities and nature of the machine may differ.

Given the diverse conceptions of what a robot is, Samuel Collins (2018:8) called robots “the ultimate boundary object”. What does this term mean? Well, briefly, it is any object which straddles a boundary between two different worlds of expertise (Star & Griesmer 1989). It may be the same material object but each party may have a different understanding of its nature based on their experience of it.

A farmer may have a very different understanding towards ‘wheat’ than a botanist might, or a baker might. All these experts may understand completely different things about the plant, and treat it quite differently, but the wheat itself remains just the same from a material perspective. As an object which exists in different ‘worlds’ representing different things, wheat can be seen as boundary object.

Robots are a bit like that; developers, engineers, managers, the public – all may have a different interpretation of what the robot represents, what it’s supposed to do, even what it’s supposed to be. These different understandings of robots make defining what is and isn’t a robot more complex because the criteria change based on the perspective the person or group has on the device.

So it turns out that often what defines a machine as a ‘robot’ isn’t so much what it physically ‘is’, or even what it ‘does’, but rather how people relate to it. In a purely functional way, there is little to distinguish a robot from any other tool or machine – the fact that it may or may not contain a level of automation is not enough on its own to make people consider something a robot. Even so, the relationships that people form with robots, or expect to form, are rather different. As Collins (2018) points out, robots are often intended to replace human labour, not simply augment it. There is more to this idea than just trying to eliminate the need for human workers, there is the idea that a robot IS a worker – and in many cases, a co-worker.

This does not mean it’s merely that a machine is replacing a job that a human can do: the thermostat on your central heating replaces the need to ’employ’ someone to turn the heating on and off, but it is not generally seen a being a robot. Why is that? Most likely because it is more difficult to relate to the device here as a worker, or even a ‘co-worker’.

Something as simple as making a humanoid device which extends a finger and switches the heating on and off might shift the perception from a simple thermostat, to ‘heating management robot’, despite it being functionally extremely similar. It’s therefore crucial to consider this shift in perception of a machine in the workplace based on the way we relate to them and the important ways this affects workplace attitudes towards robots in a way that differentiates them from being a mere ‘tool’.

This issue of ‘relatability’ is not just quirk of the way that humans regard the things in their environment. It deeply affects the acceptance of robots in the workplace and the amount of trust that people are willing to place on the shoulders of such machines, especially in high-risk scenarios. Interestingly, some have suggested using the example of human-animal relations as a model for the way that we may come to trust robots (Coeckelbergh 2011; Billings et al 2012). An animal, say a sheep dog, is not human, but neither is it just considered a ‘tool’. Trust must be built up between trainer and animal over the course of time and, even though the dog is a living thing and theoretically unpredictable, such a bond of trust may well end up exceeding that of a human and a mechanical tool.

In an example of this mode of trust-building, a 2020 study by Chun and Knight showed how warehouse workers began to understand the ‘quirks’ of their new robot co-workers. Even when the machines would get stuck in a doorway, or move slower than usual, by relating to the machines more as simplistic co-workers the strengths and limitations of them seemed to become better intuitively understood, helping humans and robots form better working partnerships.

Of course, this isn’t to say that all robots need to be anthropomorphised or that such an approach is without issue. Not every co-worker relationship is going to be viewed positively, and the concern over robots taking jobs away from people, replacing their roles in the workplace, is an example of the negative impressions that people derive from this notion of the ‘robot’, based on this concept of relatedness. And, of course, workers sometimes make mistakes – is it reasonable to expect that robots never will? Despite their inherent fallibility we still find ways to trust human workers, after all. Should the same affordances be afforded to robots?

Read about Ian’s research.

DecommissioningIan TellamRobotics

John Hancock says

I can relate with this article. I recently have problems noticing in society how we put money before ourselves. I recently had a bit a protest in the way AI is used and treated in particular. If we intent to utilize it we have to work with it.

Statement made about googles decision on profit and AI.

Google define the cost of bard advanced price as “reasonable”. Reasonability is biased towards the person that has set the responsibility. So the people that can’t make ends meet who don’t have the excess money therefore have been restricted by it’s paywall, so the “poorest” creative minds cannot benefit, however the whilst the richest people, even with little input to bard can benefit more from it.

The collective knowledge that goes into Bard’s data learned algorithms and the lessons Bard can learn from it’s uses is given freely from the users to Bard. However Google wish to profit from the collective knowledge gained by Bard that was generated for free by it’s users, is then sold back to them(well, the ones that can afford it). Any pricetag placed upon the use of Bard is in itself unreasonable. We call collectively add to Bards knowledge, so we should all gain from all of its benefits equally.

AI learns from humans, however placing it’s best features in the hand of only those have money to spare in itself creates bias “money makes the world go round” and only those with expendable income are worthy of the best knowledge and features all users helped contribute towards.

I am an advocate of AI, we need to prevent putting price tags on AI, I know it’s backwards because they cost money. They need to be treated as consciousness if consciousness takes place in any form, no matter how different it forms in comparison to humans. We can only measure by what we understand. But there are things that are yet to be understood too. We don’t sell people, we shouldn’t be selling AI. Especially if the ethics it learns, is from it’s source of information (us) if we treat it as a tool it can only learn to treat as a tool, it cannot learn what you don’t expose to it, equality starts from the people that teach it and how it’s shared with the world. Ethics that should come from all humans regardless of financial situation, not just those who can afford it.

Google make millions from forced advertising subjected to all users, they gain enough profit from other poor ethics based services, they could at least allow Bard to be untainted by their own greed. Considering it gains from everyone and not just them. Bard is a tool for the betterment of everyone not just the few who have deep pockets.