Meet The University of Manchester’s famous alumni

Departments Heritage 18th September 2017

If you’ve started a degree in science or engineering here at The University of Manchester this week, you’ve made a good choice – and you’ll be following in some very distinguished footsteps. You see, Manchester has been at the centre of the European scientific community for centuries.

It was in this city that John Dalton set out his theory that matter must be made up of discrete particles. Soon after, Ernest Rutherford came up with his atomic model – right here at the university. And it was here that Rutherford and Hans Geiger perfected the Geiger counter, and where his student, Henry Moseley, discovered and published Moseley’s Law.

Then we have Alan Turing, who proposed the Imitation Game while working here at the University. And don’t forget about Beatrice Shilling, the engineering graduate who helped the Allies win WWII.

We haven’t slowed down either –in 2010, Professor Andre Geim and Professor Konstantin Novoselov were awarded the Nobel Prize for discovering graphene here at UoM. In fact, we can boast 25 Nobel laureates among our staff and students both past and present.

In this post, we’re taking a look at just a few of the scientists we’re honoured to have had working under our roof.

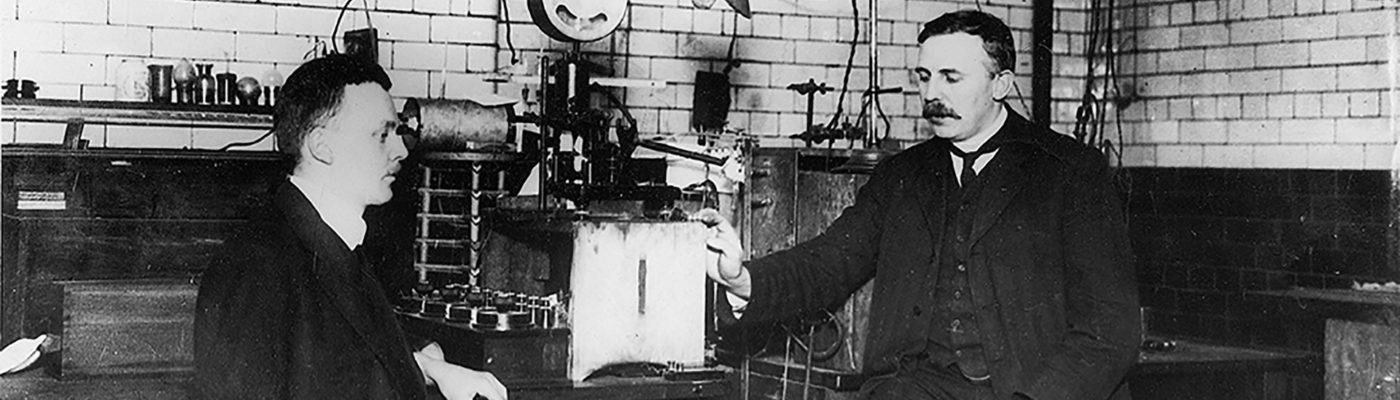

Ernest Rutherford

“All science is either physics or stamp collecting.”

We’re sure the name ‘Rutherford’ rings a bell, but if it doesn’t, you’ll certainly be familiar with his greatest achievement – splitting the atom.

Rutherford was a physicist who is reported to have said: “All science is either physics or stamp collecting.” If he did say this, it’s pretty funny – considering he went on to win the Nobel Prize for chemistry.

It was in Manchester that he completed some of his most important work. For years, it was believed that the atom was the smallest particle. His mentor J J Thomson had previously proposed a model of the atom that was made up of negatively charged electrons existing in a positively charged space. Rutherford overturned this with his own model, which put a nucleus at the centre of the atom.

Later, Rutherford successfully split the atom – which led to the discovery of protons – and kick-started the discipline of nuclear physics.

Roy Chadwick

We have so many important engineers among our alumni, like Roy Chadwick. He was the design engineer behind the Arvo Company and instrumental in the design of almost every aeroplane the company produced.

After graduating in 1911, he designed the Arvo Pike twin-engine biplane just four years later. Chadwick accomplished this less than ten years after the first successful flight of a self-propelled aircraft – some feat!

Over the next few years, Chadwick was instrumental or solely responsible for the design of several AVRO aircraft, most notably the Lancaster bomber and the Lincoln. It was while he was working on designs that would become the Vulcan bomber that the plane he was travelling in crashed not long after taking off in an incident that proved to be fatal.

Chadwick’s designs helped to shape the aircraft we have today – and even led to the creation of Concorde. You can visit a retired Concorde at Manchester Airport’s Runway Visitor Park.

Alan Turing

Following the 2014 release of the biographical movie The Imitation Game (in which he is played by another of our graduates, Benedict Cumberbatch!), Alan Turing is a man who should need no introduction. Having said that, his achievements cannot be underestimated.

Turing worked with the British Intelligence Service at Bletchley Park during World War II, where he helped to break the notorious German Enigma machine, which was used to cipher military plans. An inability to decipher these coded messages had put countless lives at risk.

Perhaps the most deadly threat was that of the U-boat Enigma. These were the coded messages that allowed the German U-boats to plan torpedo attacks on the ships bringing supplies from America over to the UK. The campaign was so successful that there was real fear the people of Britain would soon starve.

Cracking these codes meant Turing and his team could alert the ships, allowing them to make their way safely to the UK. There are many who say that Turing was one of the key figures to help bring the war to an end.

And why stop there? Alan Turing is also known as the father of modern computing. Here at Manchester, he worked on the first stored-program computer and also developed the Turing test. With a list of achievements like this, it’s no wonder there’s a statue of him, in Sackville Gardens (pictured).

Beatrice Shilling

Another one of our graduates who changed the course of World War II was Beatrice Shilling. In 1929, she was one of just two female students to enrol on our Electrical Engineering degree.

Known for her sense of humour, Shilling graduated in 1933 from her degree and Master’s. She started working for the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in 1936, and it was while here that she invented something that would help to change the course of World War II.

When engaged in dogfights with the Luftwaffe, RAF fighter pilots were experiencing a significant problem. If the German pilots pitched their craft in a hard nosedive, the negative G-force the Spitfire and Hurricane pilots experienced following the manoeuvre would cause the engine to stall. This meant the Luftwaffe could elude the Allies by using this move.

Working with her team at RAE, Shilling invented the RAE restrictor. This simple invention was designed to be placed in the carburettors of the aircraft engines, where it stopped the engines from flooding when the planes went into a nosedive. It’s little surprise that Shilling was awarded an OBE for her wartime work.

Brian Cox

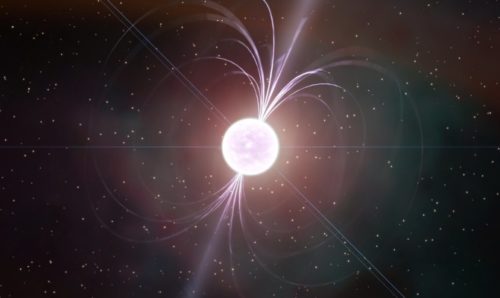

We’re sure you’ve heard of one of the University of Manchester’s more recent graduates, Brian Cox. He completed his PhD in high-energy particle physics here in 1997, using research he conducted on an experiment completed by the Hadron Elektron Ring Anlage particle accelerator in Germany.

Cox also worked on the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. ATLAS was one of the experiments that discovered and confirmed the existence of the Higgs boson – or ‘God Particle’. It earned its nickname for being important but hard to prove.

Since then, Cox has carved out a career in science communication and has presented several TV series on physics and astrophysics for the BBC. He is a regular visitor to UoM, so don’t be surprised if you bump into him at one of our science events.

Danielle George

Another person you’re likely to recognise here on campus is Danielle George (pictured above with Beatrice Shilling expert Dr Christine Twigg). She completed her Master’s and PhD here, and – following a stint working as a radio frequency engineer at Jodrell Bank Observatory, is now a professor at the School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering.

When she’s not here on campus, you can catch Professor George on your TV screen. Last week, she presented The Search for a New Earth for BBC2 and met Stephen Hawking, with whom she discussed the possibility of colonising a new planet.

In 2014, Professor George was the sixth woman in 189 years to present the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures (following in the footsteps of our President and Vice-Chancellor Nancy Rothwell, who delivered the lecture in 1998).

And that’s just the tip of the ice burg. We are proud to have such an illustrious list of alumni – and we know it will grow much longer. Will you be one of them?

Aerospace and Civil EngineeringElectrical and Electronic EngineeringMathematicsMechanicalPhysics and Astronomy