Sir William Boyd Dawkins – an extraordinary study

Dinosaurs Heritage SEES 28th January 2019

Science and engineering at Manchester wouldn’t be where it is today without the work, enterprise and discovery of those who went before us.

As we approach the next phase of our journey and the move to MECD, we at The Hub will be taking a look back in history at some of the people who’ve helped get us here – and the fascinating stories they share.

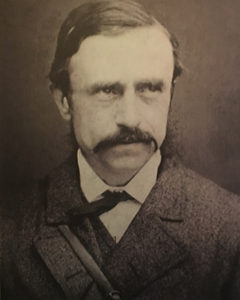

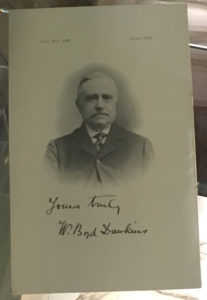

We start with the extraordinary life of Sir William Boyd Dawkins.

Dawkins at Manchester

Dawkins’ is a story of discovery and progression – both in and outside the classroom. It’s one that still resonates today; not many people, after all, have a recreation of their home study in a museum, full to the brim with exotic animal bones and artefacts!

Born Boxing Day 1837, William Boyd Dawkins would go on to become a hugely popular lecturer and influential figure in the development of geology and palaeontology at Manchester. He became Curator of the Manchester Museum and Professor of Geology at Owens College (which would later become the Victoria University of Manchester and, following the 2004 merger with UMIST, The University of Manchester as we know it today).

Appointed Manchester’s first Professor of Geology and Palaeontology in 1874, Dawkins was an innovative, forward-thinking academic, keen to stress the need for practical, hands-on learning. This led to him setting up two important laboratories: one focused on teaching-applied geology, such as geological mapping and engineering drawing; the other on fossils, mineral specimens and more.

Such was his prolificacy and enthusiasm – both in and out of the classroom – that Dawkins seemed to fit more into one lifetime than others could squeeze into two, three, four. His list of awards, for example, includes a knighthood for services to geology and the prestigious Lyell and Prestwich Medals, both awarded by the Geological Society of London.

If you think that’s impressive, check out his CV… Fellow of the Royal Society; Member of the Geological Society Survey of Great Britain; Founder and first President of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society; President of the Manchester Geological and Mining Society; President of the Anthropological and Geological Sections of the British Association; and President of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. Phew!

A life of discovery

Demonstrating a keen interest in archaeology from an early age – he collected fossils from the local colliery spoil heaps aged five – Dawkins pioneered the study of early man in Britain and went on to make a number of fascinating discoveries throughout his life.

He unearthed, for example, the marked figure of a horse’s head on a piece of bone at Creswell Crags on the border between Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. It was the earliest example of cave art found in Britain.

His work led to the discovery of the first evidence for use by Palaeolithic man (the period when humans first made stone tools) in the Caves of the Mendip Hills in Somerset. Here he also excavated the Wookey Hole Caves – now a popular tourist destination housing, among other attractions, live circus shows and animatronic dinosaurs. The location is also famous for the Witch of Wookey Hole. Legend has it that a stalagmite, human in shape, is actually a witch turned to stone by a monk from Glastonbury! Oh my.

The spooky connections continue with Dawkins’ work at another site in the Mendip Hills: Aveline’s Hole. Discovered in 1797 by two men digging for a rabbit, the cave was excavated by Dawkins in 1860. He enlarged its entrance and named it after his mentor, one William Talbot Aveline. The cave was found to be the site of Britain’s earliest scientifically dated cemetery, dating to between 10,200 and 10,400 years old, and two complete skeletons were among the more than 50 bodies found – some adorned with perforated animal teeth.

Another bone discovery, this time at Windy Knoll near Castleton, enabled Dawkins to prove that exotic animals had existed in England before the Ice Ages. They included bones from bison, a cave bear, cave hyena and a large cat – possibly related to the sabre-toothed tiger. Other forays into the world of the exotic saw him producing studies on the origins of the cave lion and the teeth of woolly rhinos.

Digging deeper

Dawkins was appointed official surveyor by the Channel Tunnel Committee for a project to build a tunnel beneath the English Channel in the 1880s – a forerunner project to the Channel Tunnel we know today. It was during this work that Dawkins made another significant discovery: the existence of coal in Kent. He advised that tunnel shafts be used to explore parts of East Kent and played an important role in the subsequent development of the Kent coalfield.

If all that isn’t enough – the academic innovation, archaeological findings and coal discovery – there’s more. Dawkins’ other achievements include work on various water supply projects, including the London water supply; reporting on the feasibility of the Manchester Ship Canal; consultation on oil prospecting and fluorspar mining; and advisory roles on oil shale in Australia, marble in Italy and diamond mining in South Africa.

Dawkins was also a philanthropist. He donated money so that an extension could be added to the Manchester Museum, was a campaigner for workers’ rights and helped locals seek compensation when their lives were affected by subsidence from salt mines in Northwich, Cheshire.

Dawkins passed away on 15 January 1929, aged 91. Even in death, however, he continues to give.

Buxton Museum and Art Gallery in Derbyshire is home to a replica of his elaborate Didsbury study and more than 400 books donated to the town of Buxton by his widow Lady Boyd Dawkins. Lined with animal antlers, sketchings, engravings, bones, the weird and the wonderful, the study is a fitting tribute to the extraordinary life of a man who gave so much – to this University and beyond.

Words – Joe Shervin

Images – Joe Shervin (taken at Buxton Museum and Art Gallery)

Be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with all the latest posts from The Hub.

DinosaursEarth and Environmental Sciencesgeologyheritagehistory

Dr Tom Welsh says

I only came across this account recently, but have myself written a short notice about William Boyd Dawkins in a book Fake Heritage:solving mysteries (Publ. Amazon Kindle in January) p240-3 and elsewhere. What amazed me about Dawkins is the magnitude of his contribution though public lectures in meeting rooms around the region. Many of these are recorded in newspapers, in some detail, and would present a worthy project for a dissertation. My particular reason for looking at Dawkins is the reliance archaeologists place on a quotation in a book: that by the use of purely inductive methods archaeologists had raised the study of antiquities to a science. However Dawkins meant something entirely different from how archaeologists read this, and not as the point at which archaeology, across the board, became a science.