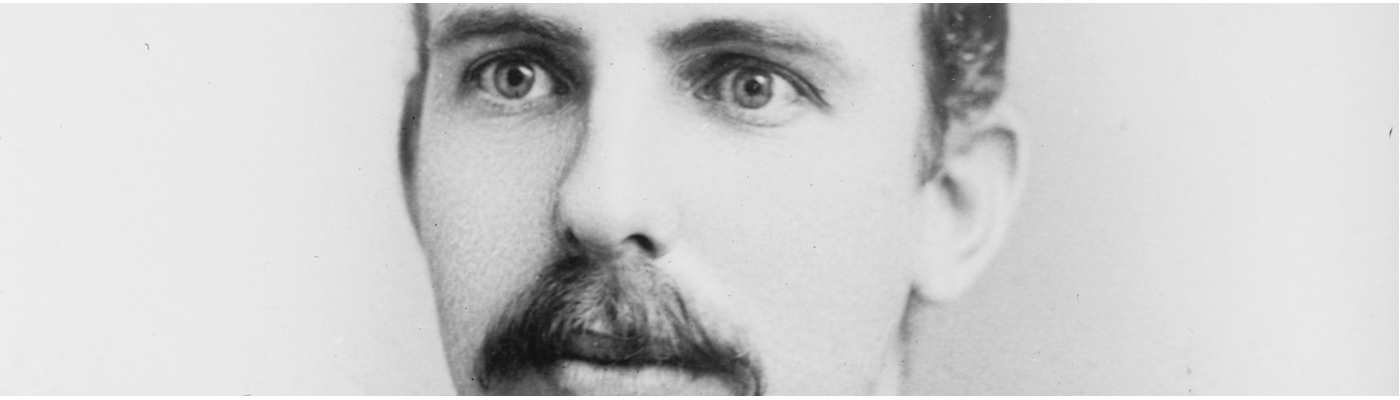

Ernest Rutherford – the ‘crocodile’ physicist who never looked back

Departments Heritage 15th October 2019

Crocodiles never look backwards. Neck stiff and strong, they go straight ahead.

Ernest Rutherford was a pioneering scientist who, not unlike a crocodile, always went forward. His many breakthroughs, including world-changing discoveries here at The University of Manchester, would transform the field of physics.

Maybe this is why Rutherford was given the nickname ‘the crocodile’ by his colleague Peter Kapitza at the University of Cambridge. Perhaps – and as offered by that university’s website – it was Kapitza’s fear of Rutherford biting off his head. Or maybe it was that Rutherford’s booming voice could be heard before his arrival, similar to the crocodile’s alarm clock in Peter Pan…

Whatever the reason, the name is certainly apt for someone who, despite appearing from a bygone era – he passed away 82 years ago this month – remains an enduring figure today. Rutherford is widely regarded as the father of nuclear physics; the crocodile, meanwhile, is a symbol of the father in Kapitza’s home country of Russia.

Rutherford’s influence is such that his many, many achievements have already been covered in great detail elsewhere. He is one of the University’s Heritage Heroes, and recently we marked 100 years since his most important breakthroughs. He’s best known, perhaps, for his work in ‘splitting the atom’ – though there is some debate whether this is the most accurate way to describe this work – studying radioactivity and, effectively, creating the nuclear physics discipline.

In this post we want to look at the man himself; his upbringing, beliefs and – importantly – some of the quirkier parts of his story.

Family and farming

Ernest Rutherford was born in New Zealand in August 1871. His parents, James and Martha, had emigrated there as children, from Scotland and England respectively. They would have 12 children together (they planned “to raise a little flax and a lot of children”) and Ernest would help with the farmwork.

Known as Ern to his family, Rutherford’s name was misspelled ‘Earnest’ when his birth was registered – a premonition, perhaps, for his future seriousness and pursuit of scientific advancement. His mother was a huge advocate for education and ensured each of her children received one, teaching them all to read and write. His father was a millwright, wheelwright and farmer, and Ernest would credit working on the farm for his inventiveness in later life.

The young Rutherford enjoyed the open-air country life, and the hard work it demanded. He would soon move on from these humble beginnings, however, to make his mark in the world of academia, famously stating: “I have just dug my last potato!”

Educating Ernest

Rutherford won a scholarship to Canterbury College at the University of New Zealand, where he gained three degrees and invented a new form of radio receiver. He would then head to England, having been awarded a Research Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851.

The fellowship took him to the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, where he became one of the institution’s first ‘aliens’ – a researcher without a Cambridge degree. Rutherford’s enthusiasm would make an instant impact, with new colleague Andrew Balfour saying of him: “We’ve got a rabbit here from the Antipodes and he’s burrowing mighty deep.”

He studied under the physicist JJ Thomson, who first discovered and identified the electron, was born in Cheetham Hill here in Manchester and studied at Owens College (now The University of Manchester). Rutherford would later propose a solar system-like model for the atom, with electrons orbiting a nucleus – similar to planets around a sun. This contrasted with Thomson’s earlier ‘plum pudding’ model, which proposed an atom comprised of negatively charged electrons in a positively charged space.

At the Cavendish Laboratory Rutherford would briefly hold a world record – for the distance over which electromagnetic waves could be detected – only to discover his results had been bettered when presenting them to the British Association. He would later take up a professorship at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where he coined the terms alpha and beta ray to describe the two distinct types of radiation, before his next big move: to Manchester.

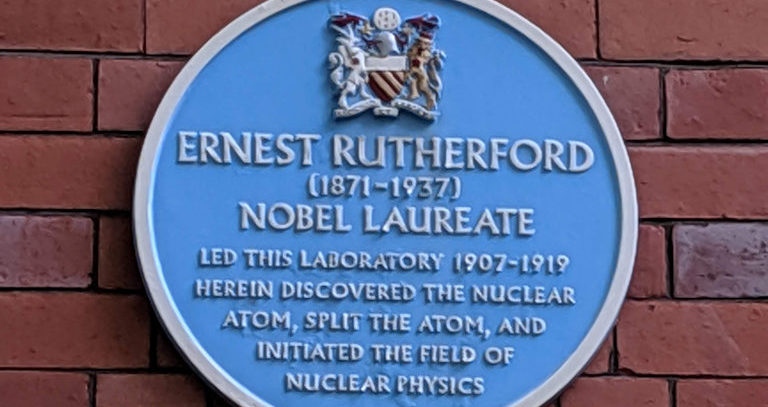

Rutherford at Manchester

It was at Manchester that Rutherford ‘split the atom’ – performing the first artificially-induced nuclear reaction, discovering the proton and changing physics forever. Of the breakthrough Rutherford said he had “broken the machine and touched the ghost of matter”.

While based at Manchester Rutherford collected a Nobel Prize ‘for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances’ – work from his time at McGill University. The prize was for chemistry, however, and there are suggestions that, being a physicist – he was Langworthy Professor of Physics at Manchester – Rutherford was a little put out to be classified this way. He did, after all, once state: “All science is either physics or stamp collecting!”

Recently on The Hub we’ve delved into the lives of various individuals after whom buildings at The University of Manchester have been named – including the Kilburn Building, James Lighthill Building and Morton Laboratory, even the Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank – and such was Rutherford’s impact here that the Physics Laboratory, where Rutherford conducted his groundbreaking research on atomic physics, was renamed the Rutherford Building in 2006.

The building dates back to 1900. It was created by Arthur Schuster, a former graduate of Owens College and professor at the University – and the man after which the Schuster Building, today’s home of the Department of Physics and Astronomy, is named.

Rutherford arrived at Manchester in 1907 as Schuster’s successor. He would transform the department, building a team that would effectively create nuclear physics. This team included, among others, Hans Geiger, who would go on to co-invent the Geiger Counter for detecting radioactive emissions, and James Chadwick, after whom the University’s James Chadwick Building – home to part of the Department of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Sciences – takes its name.

Today, Rutherford’s private research room remains in the building – and there are suggestions that his old desk still contains the tiniest traces of radioactivity. In 2009 an independent commission even looked into the possibility of a string of illnesses among workers in the building, including pancreatic cancer, brain cancer and motor neuron disease, being linked to very slightly elevated levels of radiation related to Rutherford’s experiments – but these were ruled simply a coincidence.

The building will forever be known as the site of some of the 20th century’s most important scientific discoveries – driven over a ten-year period by Ernest Rutherford. Upon leaving Manchester in 1919, Rutherford would return to Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, succeeding his former mentor JJ Thomson.

A celebrated man

Rutherford’s achievements are almost too many to mention here. Of particular note, however, was a knighthood in 1914, and he served as President of the Royal Society between 1925 and 1930. He was appointed to the Order of Merit in 1925 and raised, in 1931, to the peerage as Baron Rutherford of Nelson, of Cambridge in the County of Cambridge. For his coat of arms he nodded to his homeland with a design that included a kiwi and a Maori warrior.

Today Rutherford’s name lives on through a huge array of items named in his honour. Manchester obviously has its own Rutherford Building – and the Rutherford Lecture Theatre in the Schuster Building – yet plenty more examples are to be found around the world, including his old stomping grounds at McGill University and the University of Cambridge.

In fact, the old Cavendish site at Cambridge features a striking image of a large animal on the side of one of its laboratories. Commissioned by Peter Kapitza, the carving is in honour of his old friend Rutherford and is, you guessed it, a huge crocodile.

The element rutherfordium is named after Rutherford, so too is the Rutherford Medal, the highest science medal awarded by the Royal Society of New Zealand. His reach, you could say, is out of this world, with craters on both the Moon and Mars bearing his name.

Rutherford’s image even appears on a church stained glass window in Hastings, New Zealand. He sits beside Sir Edmund Hilary, Charles Upham and John Rangihau in the Good Man window of the Presbyterian chapel at Lindisfarne College – four examples depicting a ‘good man’.

Helping others

It’s to Rutherford’s credentials as a ‘good man’ that we now turn. Perhaps less well known about Rutherford – in contrast to his wider impact in science – are his social and political beliefs.

During his time at Cambridge University he campaigned for women to share the same privileges as men, and he also supported freedom from government censorship for the BBC. During World War I he campaigned for the US government to allow young scientists to carry out research rather than be sent to the front line.

In his home country of New Zealand he called on the government to better support research and education. This would play an important role in the subsequent establishment of the country’s Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

Rutherford spoke during World War I of his hope that not until man was ‘living at peace with his neighbours’ would the full energy of the atom be extracted and used. He also declined from working with the chemist Fritz Haber, who had helped in the creation of chemical weapons during the conflict.

Vehemently anti-Nazi, Rutherford in 1933 – while serving as the president of the Academic Assistance Council, an organisation set up to assist academics forced to flee the Nazi regime – helped almost 1,000 university refugees in their escape from Germany.

A fitting resting place

Rutherford’s death came unexpectedly, in 1937. He had suffered with a small hernia for some time prior to his passing, but had neglected to have it treated. He fell very ill when the hernia became strangulated, and died four days after an emergency operation. He was 66.

Following cremation, Rutherford’s ashes were buried in Westminster Abbey close to the tombs of some of Britain’s most eminent scientists – including Isaac Newton. It’s a fitting resting place for a farmer’s boy done (very) good; someone who arguably kick-started curiosity-driven science and was described by no less than Albert Einstein as ‘a second Newton’.

His contribution to science cannot be overstated; his contributions changed the face of physics. You could say, he gave it some real teeth.

Not unlike, a crocodile.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with the latest posts from The Hub.

Words: Joe Shervin

Images: Joe Shervin, The University of Manchester, Wikimedia Commons (Materialscientist and Steff)