Alan Turing – did you know?

Departments Heritage 20th February 2020

Recently on The Hub we delved into a lesser-known side of Alan Turing: his philanthropy. It got us thinking about what else people might not know about the maths genius who helped develop modern computing at The University of Manchester. So we did a little research – and this is what we found…

Exceptional promise

Turing’s abilities were evident from a young age. Speaking of the then-nine-year-old, his headmistress at St Michael’s Primary School in Hastings stated: “I have had clever boys and hard-working boys, but Alan Turing is a genius.”

His interest in chess began at Hazelhurst Preparatory School, where he spent hours alone solving complex chess problems. Later in life he would be credited with designing the world’s first computer chess program: Turochamp.

Aged 13, Turing headed to Sherborne School, a boarding school in Dorset. His very first day, however, fell within the nine-day General Strike of 1926, scuppering his chances of attending. Undeterred, the teenager raced off for school on his bike – and rode the 60 miles from Southampton to Sherborne alone, stopping overnight at an inn.

Physical prowess and determination

It was far from the only time his physical prowess and determination would impress. In fact, he was an avid long-distance runner – and was so good that he tried out for the 1948 British Olympics team. Hampered by injury on the day, he didn’t qualify for the team; yet his marathon tryout time was only 11 minutes slower than that registered by British silver medallist Thomas Richards.

Turing ran to relieve the stress of his work, and was even known, during his time at Bletchley Park, to run up to 40 miles for meetings in London. Members of Walton Athletic Club invited him to join their club after he overtook them a few nights earlier, noting his exceptional speed and hard, grunting style. While at King’s College, Cambridge, Turing ran along riverside footpaths between Cambridge and Ely; the annual ‘Turing Relay’ would later be held there in his honour.

He enjoyed rowing and sailing, and continued to cycle – often riding his bicycle to and from Bletchley Park. Colleagues would later recall a fault with his bike that meant the chain regularly fell off – rather than getting it fixed, however, he figured out how to correct it on-the-move, and counted the number of times the pedals went round before adjusting the chain by hand. A sufferer of hayfever, Turing was also known to cut an especially peculiar figure in the first week of June each year, when he would cycle to work in a gas mask to keep the pollen away.

The eccentric ‘Prof’

The eccentricities didn’t end there. He was called ‘Prof’ by colleagues at Bletchley Park, and ‘Prof’s Book’ was the name given to his works on the Enigma. Turing was also said to have chained his mug to the radiator pipes, preventing anyone else from using it.

While at Bletchley Park he proposed to a woman named Joan Clarke, a colleague in Hut 8. Clarke, also a mathematician and cryptanalyst, agreed to the marriage. The engagement did not last, however; Turing revealed his homosexuality and couldn’t proceed with the wedding. Perhaps the revelation wasn’t too much of a shock to Clarke, though, who was said to be ‘unfazed’ by the admission.

Turing joined The University of Manchester in 1948, taking up a role as Deputy Director of the Computing Laboratory. And it was in 1950 that, in a famous paper entitled Computing Machinery and Intelligence, he first addressed the issue of artificial intelligence – or AI.

In it he developed a method to determine whether a machine can be ‘intelligent’ by showing behaviour; this was called the ‘Imitation Game’, and is now known as the ‘Turing Test’. The Imitation Game is the name, of course, of the 2014 film based on the biography ‘Alan Turing: The Enigma’ by Andrew Hodges and starring Benedict Cumberbatch – himself a graduate of this University. The paper would have a significant influence on AI, a research area that continues apace today.

A tragic, mysterious end

Turing is remembered not only for his achievements in life, but also the tragedy of his death. He was found dead at his home in Wilmslow on 8 June 1954, aged just 41 – and mystery still surrounds the circumstances of his passing. An inquest determined he had committed suicide, and cyanide poisoning was established as the cause. Many believe he did so by eating a poisoned apple (one, half-eaten, was found next to his bed), and some even suggest he wished to re-enact a scene from his favourite fairy tale, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, in which the Wicked Queen dips an apple in a poisonous brew.

It was two years earlier, in 1952, that Turing was charged with gross indecency relating to the anti-homosexuality laws of the time. After reporting a burglary to the police, Turing acknowledged a sexual relationship with a man named Alan Murray who, it turned out, was an acquaintance of the burglar. Turing would avoid prison, but at great cost: he accepted chemical castration.

There has been plenty of speculation as to whether Turing did indeed take his own life. The apple found in Turing’s room was never tested for cyanide (and it was not uncommon for him to eat one before bed), while his mother held that the cause had been accidentally-ingested cyanide from his fingers following an amateur chemistry experiment.

Prior to his death Turing had insisted, while on a day trip to St Annes-on-Sea, on seeing a fortune teller. It was not the first time he had done so; as a child he visited a fortune teller who predicted he would be a genius. It is not known what was discussed during this later visit, but those with him reported a darkening in Turing’s mood when emerging from the tent. There have even been suggestions linking what he heard with the tragedy to come.

Some people erroneously assume that the logo of multinational technology company Apple – an apple with a bite taken out of it – is a homage to Turing, who is widely considered the ‘father of computer science’. When asked whether the design of the logo was intentional, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs apparently replied: “God, we wish it were!”

Appreciation, at last

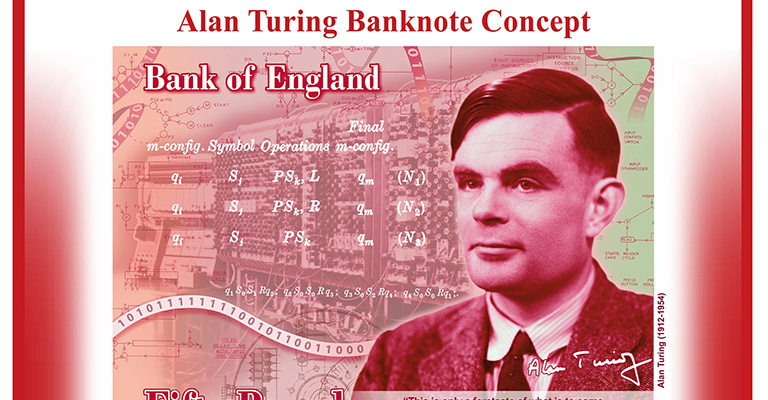

Turing’s incredible work may have been overlooked during his lifetime, but it is widely celebrated – and certainly appreciated – today. In 2013 he finally received a royal pardon after many campaigned for it, including world-famous physicist Stephen Hawking. Fellow national treasure Stephen Fry said at the time: “At bloody last, next step a banknote if there’s any justice!”

Fast forward to today and, of course, that call has been answered. Alan Turing has been chosen to appear on the new £50 banknote, expected to enter circulation next year.

What better way to commemorate such a brilliant and eccentric, yet ultimately tragic, British hero?

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with the latest posts from The Hub.

Words: Joe Shervin

Images: Dunk, Richard Gillin, Bank of England, Wikimedia Commons