Climbing the iconic Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank

Heritage UOM life 15th March 2023

It emerged above the trees as we neared the site.

That gleaming, white, unmistakable dish.

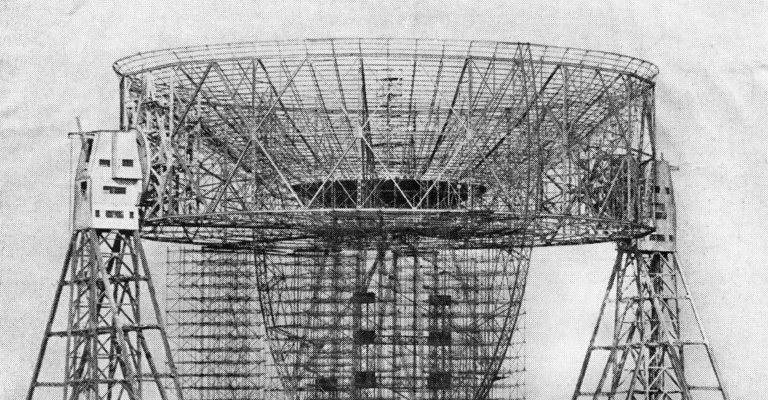

Like a silhouette in a Star Wars backdrop, appearing – somehow – both historic and futuristic. A huge bowl, cradled by criss-crossed girders and two great towers.

Pointing straight up to the sky, the famous Lovell Telescope was, today, parked for maintenance – and we were going to climb it.

What a dish!

Visible, on a clear day, from the Beetham Tower in central Manchester, and as far away as the top of the Pennines. Even – if you squint – from Snowdonia.

A giant, Grade 1 listed sphere, glimmering in the Cheshire countryside.

It boasts a 76-metre-diameter reflecting surface and continues, to this day, to investigate wondrous cosmic phenomena – much of it inconceivable when the telescope was first built.

But, how does it work day-to-day?

How is it maintained?

Who are the people keeping it working and, crucially, keeping it safe?

In the second of our special series on Jodrell Bank we’ll take a closer look at the engineers who keep the site ticking over. But first we recount the unforgettable experience of scaling the immense, beautiful – at times scary! – structure that we all know and love…

Don’t look down…

Jodrell Bank is, of course, part of The University of Manchester and sits within our Department of Physics and Astronomy. Here on The Hub we’ve previously delved into the life of the man behind the famous telescope, Sir Bernard Lovell; documented our trip to the wonderful Bluedot Festival; even discussed the time Doctor Who came to visit.

But never have we been fortunate enough to climb the dish itself.

Entering the site we are greeted by Neil Roddis, Head of Engineering at Jodrell, who has kindly agreed to show us around (and up!).

It’s hard hats on and nerves steeled as the four of us squeeze into a small lift. We disembark up the Green Tower – the Red Tower is mirrored on the other side – and get a first glimpse of just how high we are (clue: very!).

A cold-yet-sunny day, we’ve an almost birds-eye view of the sprawling Jodrell site below. A gaggle of visiting schoolchildren can be seen – and just about heard – as they move and chatter below, and a panoramic view is obscured only by the forest of beams and girders that keep the giant bowl in place.

Walk This Way

The narrow walkway to the middle of the structure is certainly not for the fainthearted, and it’s at this point we lose one of our party (he didn’t fall or anything, rather reached his vertical limit!).

Rust and peeling paint are evident from within the behemoth structure – and it’s clear that looking after such a construction is a mammoth, ongoing task.

For instance, parts of the telescope are painted over the summer months each year to combat corrosion of the steel structure. It’s just one on a huge list of tasks – some routine, daily; others unexpected, sporadic – to be ticked off.

Our numbers are replenished when we meet Phil Clarke, Head of the Telescope Workshop Team, in the structure’s core.

Phil is one of a small number of engineers who look after the day-to-day running of not only the Lovell Telescope, but also the smaller telescopes dotted throughout the grounds, plus the 25-metre and 32-metre diameter radio telescopes comprising the e-MERLIN network. Together they form an array of seven radio telescopes, across Britain, connected by a dedicated superfast optical fibre network, and boasting an angular resolution comparable to that of the Hubble Space Telescope.

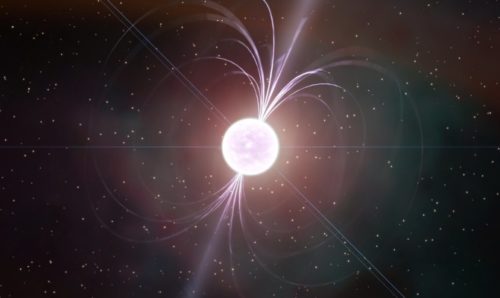

The work is essential, and safety paramount. So too, of course, is ensuring the mind-boggling technology – capable of carrying out, as an example, detailed investigations of distant pulsars – remains in full working order.

Incredibly, the site is manned by a team of Telescope Controllers 24/7, 365 days a year – ensuring round-the-clock observation and safety. On the Lovell Telescope, engineering inspections are carried out daily.

Such is the team’s vast experience within the Lovell structure that they know every creak and bang – and can usually tell, by ear, if anything’s amiss.

Past, present and future

Preservation of the site’s awe-inspiring heritage is imperative.

In 2019, Jodrell Bank Observatory was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage List – and it’s easy to see why.

Construction of the Lovell Telescope – originally known as the 250ft Telescope – was completed in 1957. As the name suggests, it’s a colossal structure. In fact, when first built it was the largest steerable dish radio telescope in the world. Even today it remains the third biggest.

Its maximum height above ground is 93 metres, while the mass of the bowl alone is 1,500 tonnes, and the mass of the whole telescope a massive 3,200 tonnes.

Throughout its time Jodrell Bank has, of course, been the site of groundbreaking research and important discovery.

From tracking Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite, in 1957, the year of the telescope’s unveiling, to tracking both US and Soviet probes during the famous Race to the Moon of the 1960s, to discovering quasars and its seminal work on pulsars, meteors and gravitational lenses, Jodrell Bank has seen it all.

And its towering contribution to astronomy continues to this day.

In 2021 the site was confirmed as headquarters to the Square Kilometre Array – the largest radio telescope network in the world – and also serves as the e-MERLIN National Facility headquarters.

Additionally, it will soon carry out tests on a telescope destined for the Atacama Desert in Chile as part of the SO:UK project, a major UK collaboration under the direction of Principal Investigator Michael Brown, Professor of Astrophysics at Manchester.

A new state-of-the art receiver will be built in Manchester to supplement the existing Simons Observatory, the next-generation Cosmic Microwave Background Observatory, and Manchester will also host the UK-based data centre.

But, back to the present – and it’s almost time to climb into the dish…

Centre stage

First, Phil tells us about the inner workings – the nuts and bolts (of which there are many!) – of the telescope. He points out, as we stand in the structure’s centre, that there is, in fact, one ‘dish’ beneath our feet and another above our heads.

The one below is the old surface; the one above the new. As Phil explains, a great deal of work has recently gone into the relaying of the older to ensure its structural integrity.

He also shows us a cryogenic receiver stored between the bowls. Cryogenics (cooling to -260 C) are used to achieve the extreme sensitivity necessary to observe radio signals from distant stars and galaxies. Two different receivers are used, each covering a particular range of frequencies, and these are swapped over at intervals of a few weeks, the changeover taking a few hours and a lot of physical effort by Phil’s team.

Interestingly, Phil and Neil tell us about (and later show us) a new mechanism being constructed in the site’s workshop. It will have the capacity to switch between the two receivers automatically, saving the team the arduous and unenviable task of scaling the antenna and hoisting the cryostat to make the switch manually.

And we soon discover just how difficult a job that would be – as we ascend the narrow ladders and emerge into the brilliant white light of the famous big bowl.

Super bowl

We pop up, blinking, awash in the gleaming bright light. It’s a beautiful day, sunny but cold, and our eyes readjust as the sun bounces off the curved surface.

The telescope is parked with the dish facing upwards, meaning we’re surrounded by the white of the bowl and blue of the sky. Standing tall in the centre is the huge antenna, piercing the air and marked by small steps leading up.

We’re very high, but scaling the very top of the antenna is out of the question for us mere visitors. We’ll leave that to the professionals – a climb they’re often required to do when the work demands it.

Standing at the foot of the looming antenna, in the surreal setting of the great Lovell Telescope, really drives home the skill of the engineers who work on the structure day in, day out.

Listening as they casually describe their work, the value of their stellar contribution to the running of this wondrous facility is as clear as the blue sky above.

Twin Towers

After a lengthy chat within the bowl, hands numbed and treading carefully to avoid a slip on the glistening surface, we descend the vertical ladders (with Neil and Phil kindly offering to carry our camera), and head back towards the Green Tower.

Here, we encounter some even taller, steeper ladders – and the opportunity to climb to the very top of the tower. We slowly, carefully, edge up, and Neil and Phil swiftly, expertly, follow.

At one level we learn the fascinating histories of the drive gear sets – they were, in fact, gun turrets from the battleships HMS Revenge and Royal Sovereign – and at the highest level we’re shown one of the secret ingredients that enable this mammoth steerable radio telescope to move: grease.

In fact, there’s a huge tub of it – and Phil explains how they apply it to the racks by hand. Literally ‘greasing the wheels’ to keep the magnificent structure gliding as it should.

We head back down the steel ladder with great care – thawing hands grip metal rungs tightly – and say goodbye and thank you to Phil. The four of us then cram, once again, into the lift.

A few seconds later and we’re at ground level once more (phew!).

Out of this world

What a fantastic honour to climb such an iconic structure!

Not only was it incredible to scale the telescope itself, but to also meet the remarkable engineers who keep it functioning and safe.

In the next of our series we’ll discuss the vital work they carry out across the wider Jodrell site.

But back on solid ground and it was time to peer up, once more, at that beautiful bowl, and say thanks to Neil for his time and hospitality.

To recognise the ‘ordinary’ work that facilitates the seamless running of a truly extraordinary site.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with the latest posts from The Hub.

Words: Joe Shervin

Images: Kory Stout, Joe Shervin, Rachel Hobson, The University of Manchester

Jodrell BankPhysics and AstronomySpace

Lynn Shervin says

Fascinating stuff Joe!….. and all within a few miles of where we live..

Shirleyann Broderick says

So interesting, lovely words ,Thankyou so much, never realised Jodrell Bank had so much history

Paul Stone says

You are so dishy

Jackie Simsolo says

Fantastic, such an interesting read x

Ada Snape says

Brilliant, interesting read never realised how big and vast this was

Rose says

Loved reading this!

Russell Kirby says

Any chance I can do the climb sometime?

Michael Shortland says

I graduated at UMIST in 1956 and remember how controversial the proposal to build the dish was in those days. Prof Lovell had a vision of receiving signals from outer space that few shared. We are fortunate that he stood his ground and won the day.

Leo Yurevich says

Fascinating engineering and achievements! Pity, while in Manchester, missed that wonderful facility.

Peter Hanley says

About 55 years ago when I was doing research at UMIST, we had a Russian visitor. I took him out on a trip round the countryside and we stopped at Alderley Edge. From there we had a great view of Jodrell Bank and I told him that there was the world’s biggest steerable radio telescope, which had tracked his Sputnik.

He didn’t believe me!

Shouvik Datta says

Yes, this is a great network and collaboration. The UNESCO badge is also very important.