Mountain safety: student ambassador insights

Student experience 21st January 2021

Student Ambassador Olivia Heard relates an unusual experience in the great outdoors, which took place last year. As we turn to outdoor pursuits for exercise and recreation, Olivia shares her story to reiterate the importance of mountain safety.

As a student studying both geography and geology, wild camping in the outdoors is often something that makes me feel really connected to my degree programme. But following an incident last summer, I felt just a little too connected when what must have been 60 mph winds swept up my tent (with me inside), rolled down a small ledge and landed straight into the edge of a lake. During early September last year, I had gone on a well-planned solo trip, camping at Levers Water, below the summit of Old Man of Coniston in the Lake District. As a wild camper with over 6 years experience, I had gone up well prepared, on a busy weekend, after double checking the mountain weather forecast which predicted 20-30 mph winds and light rain. One challenge after another appeared that night – watch the video below to find out what happened.

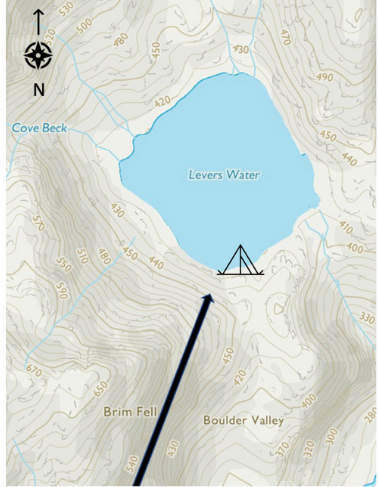

You are probably wondering, how on Earth did the winds get so strong when they were only forecasted at 20-30 mph? I like to think this is where my geographical and geological background comes in. After a good night’s sleep, I took out the map the next day to show my Auntie, Fenella (who helped me on the unsuccessful tent rescue mission), and she pointed out two hill formations with a tall, narrow escarpment in between them. From my lectures on sedimentology and geomorphology, I took an educated guess in thinking that the southerly winds from the brewing storm over night (un-forecast until the next day), had focused through the narrow formation, picked up speed, and placed my camp site directly in the firing line.

It is extremely unlikely that a situation like this one will ever happen to you, even amongst campers this sort of thing does not happen very often. But there is still a message I’d like to pass on to other students, and I hope even more that it comes into practice if COVID-19 does not restrict travel again. As you already know, your group and independent field trips may take you into remote locations such as the one I hiked in. You might be taking sediment cores from cirques below mountain summits, or visiting an island off the coast of Scotland to conduct an independent mapping project. During these excursions there could be no shop to pop into if you get cold, or even signal to phone for help in the event of an emergency. When travelling in an area outside of your comfort zone, you must be prepared. It was this preparation and experience which kept me calm during my ‘lake swim’ and allowed me to pull myself out of a sticky situation, and so the following advice should just serve as a reminder of what you probably already know.

- Plan your route

Know how to get there and know how to get back. Will the tide restrict your time to collect samples during the day? Will you have to travel there without a car? Does the walk cross steep terrain to get to your field location? And how long will the trip take? Know your limits. It is often those who underestimate how long a walk takes, that end up calling mountain rescue.

- Don’t navigate from a phone

This is a common way in which people get lost. Although it may be tempting to follow that little arrow on google maps, it will run down your phone battery, it won’t tell you where to safely cross streams, where the footpath changes direction, or give you a six-figure grid reference for mountain rescue. If you don’t know how to map read, then that’s okay, but learn how if you need to.

The following link is a good introduction on the basics https://getoutside.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/guides/beginners-guides-map-reading/

- Take spare clothes/waterproofs

If the brutal weather beckons and you still have your sedimentary logs to complete, you’ll be grateful that you took your waterproof coat and trousers when you’re soaked through after a hard day’s work in the field.

- Bring lots of snacks

“Eat your snickers, you’re not you when you’re hungry”. Empty stomachs can lead to rash decisions, especially if you’ve gotten lost.

- Have a back-up plan

Make sure you know where to retreat in the event of really bad weather or injury, for example, this might be a car, or a nearby town. It’s also wise to let people know exactly where you are (on a map) and how long you’re going to be there for before your trip.

Olivia Heard is a BSc Geology and Geography student in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. Our Earth and Planetary Science undergraduate degree has a Geology with Physical Geography pathway within the programme.

cirquesescarpmentgeomorphologyhigh windshill formationsmap readingmapping projectmountain safetyoutdoorspreparationsediment coressedimentologywild camping

Leave a Reply