Rocks in the African desert: fieldwork in Angola, part 1

Student experience Welcome to EES 14th October 2019

In the first of two blog entries, Dr Stefan Schröder takes us on an African fieldwork expedition with PhD students from Earth and Environmental Sciences, Manchester…

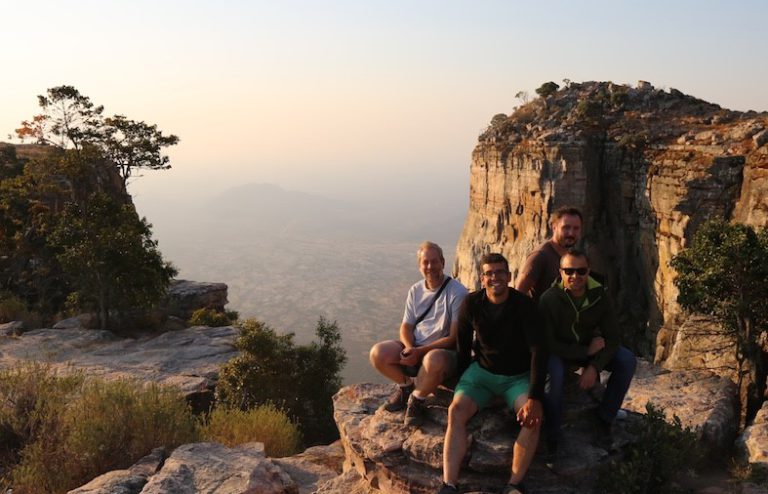

Most geologists will probably say that fieldwork around the world is the bread and butter of a geological career. As fieldwork locations go, Angola will probably rank among the more unusual places. Also, due to its recent history of a long independence and civil war, not many geologists have worked here since the 1960s. In September, I accompanied 3 of my PhD students working on the geology of Angola on our first ever field campaign to the southwestern part of the country between Lubango and Namibe cities.

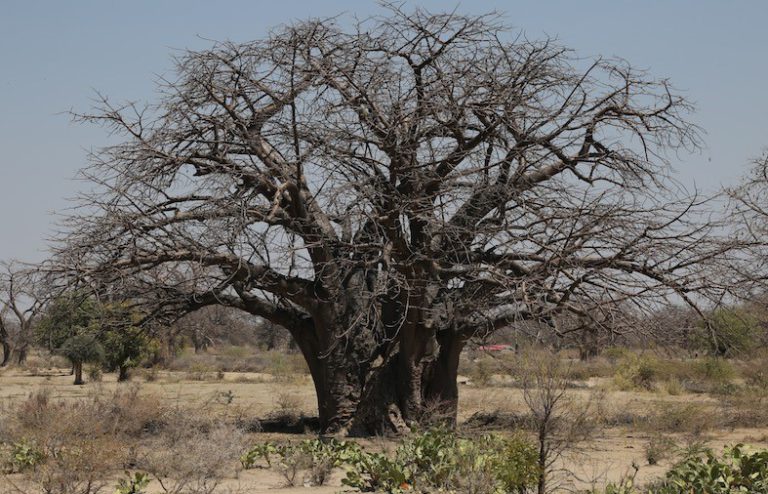

We set off on our journey in northern Namibia – despite the long access, this turned out to be logistically the simplest. Northern Namibia is underlain by the Damara Orogen, a late Precambrian mountain belt formed by collision between the Kalahari Craton in the south, and the Congo Craton in the north (a craton is an ancient block of continental crust). We are driving north from one ancient landmass to the other, although there is frankly very little outcrop to tell you about. A couple of hundred kilometres into Angola though, Archean and Proterozoic granites appear as inselbergs either side of the road. The setting is classic southern Africa (Gondwanaland as my own supervisor once said to me): large-scale peneplation dotted with more resistant inselbergs. Small villages with baobab trees lie in between. This is as rural as Angola gets, but the granites are quarried for decorative and building stones, and exported all the way to Europe. The infrastructure helps – the roads either side of the border are impeccable (with short potholed exceptions).

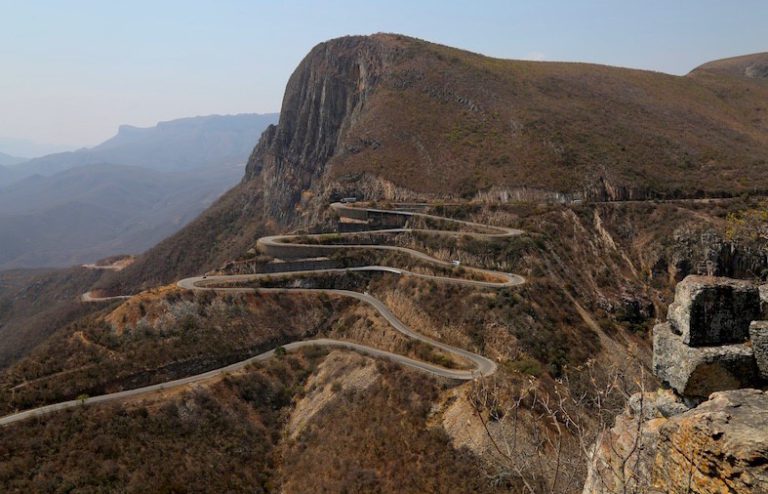

Eventually we reach the city of Lubango, but we press on, because the coast is our aim. That next stretch of road must be one of the most spectacular in Africa – the Serra da Leba road drops 1000m down the Great African escarpment. This escarpment can be traced from central Angola round southern Africa to Moçambique. It reflects erosion due to continental-scale uplift in southern Africa since about 30 million years ago. Whatever the underlying geology, the winding road is a pleasure to drive and affords great views.

A surprise then waits at the coast – although this is the northern tip of the Namib desert (perhaps the oldest desert in the world, and arid conditions may have been established here 55 million years ago), we get – rain. Although rain may be a strong word – it is more very fine rain drops that descend from a mist all around us. The hot desert air meets cold Atlantic air carried north by the Benguela oceanic current. This results in a common layer of mist or fog that only extends a few kilometres inland, but brings vital moisture to plants and animals living in the desert (like Welwitschia plants). The benefit for us – ideal temperatures for field work.

Join us next week for part two, where we will hear from Dr Schröder on the geologic process of rifting, the adventure of desert camping and some surprising fossil finds.

AngolaBaobab treeGeologygraniteGreat African EscarpmentInselbergslimestoneNamib desertPhDPrecambrian mountain beltsandstoneSerra de Leba mountain passstudy

Leave a Reply