IWD2019: How young women of STEM are restoring the balance

Social responsibility Uncategorized 8th March 2019

A balanced world is a better world. A world where all people are equal and equally represented. A world where achievements made by different people from different backgrounds receive equal recognition.

And that’s why this year’s International Women’s Day campaign theme is Balance for Better – not only celebrating the achievements of women, but also taking action for equality and raising awareness against bias. And nowhere is this more important than in the scientific community.

A woman who matters

“Even though you feel like you’re very small, you can have a huge impact on the way that people perceive science,” Dr Jess Wade.

This week, The University of Manchester was lucky enough to receive a visit from Dr Jess Wade. A physicist at Imperial College London, Dr Wade is a woman who matters – and that’s on the record! Last year, the journal Nature included her in its annual Nature’s 10 list – a countdown of ten people who matter in science. On top of that, she won the Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining (IOM3) Robin Perrin Award for Materials Science in 2017, and the Institute of Physics (IOP) Daphne Jackson Medal and Prize in 2018.

But Dr Wade is probably the last person to hold herself up as a Wonder Woman of science, or someone who will single-handedly reverse the gender inequality that has blighted the discipline for decades. In fact, if you ask her, we’re all in this together (to quote High School Musical).

“I think people are doing things incredibly differently now and young women are really driving the change,” Dr Wade told an enraptured audience at this week’s Balance for Better event, organised by the Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health.

“Even though you feel like you’re very small, you can have a huge impact on the way that people perceive science, scientists and also the way that young people access education.”

And it’s true – no matter how big or small your efforts, they all help make the scientific community a better, more inclusive place for everyone.

Winning at Wikis

While Dr Wade has won numerous industry accolades, both for her public engagement work and her research into polymer-based light emitting diodes, she’s also been tirelessly chipping away at the lack of representation of women and black and minority ethnic (BAME) scientists over on Wikipedia. Every day, Dr Wade adds pages and makes changes to the colossal online encyclopaedia in order to give fair dues to the scientists responsible for huge discoveries and developments – only to be overlooked by their own peers.

Nine out of 10 Wikipedia editors are men, which may explain why women account for just 18% of people profiled on the site – unconscious bias in all its glory. With female representation on Wikipedia roughly matching that of the recognition of women on banknotes, Dr Wade has found herself inspired every day as she learns about the women she adds to Wikipedia.

While she started out writing a page a day, Dr Wade soon had a gang of volunteer editors working on content to make it more inclusive. Work like this helps to create a record that looks more like the world we live in – one where women make up half of the population. And editing Wikipedia is something anyone can get involved in.

Yet there is still more work to do. “When you look at the data, it’s really frightening and nothing is changing at the speed you want it to,” Dr Wade explains.

Battling trolls

As we’ve mentioned before (on more than one occasion – in fact quite regularly), the underrepresentation of women in science is a complicated problem – and one that starts young. In fact, many an internet troll would have you believe that the fact only a fifth of girls study Physics at A level and only 6% of Physics professors are women is because, simply, there are more genius men (really!). And yet research has shown that in science, girls consistently outperform the boys.

“Trolls on the internet say there is a difference in our biology – but there is absolutely no difference in our biology,” says Dr Wade. And in fact, over a century ago in the UK, it was the girls who were making waves in science. Citing the work ‘A Chemical Passion: The forgotten story of chemistry at British independent girls’ schools’*, Dr Wade reveals that at the turn of the 20th century, it was the girls who invested in their scientific studies.

Girls would travel by horse and cart to learn in real industrial facilities, specialising in chemistry and the physical sciences. But then a report was published that warned that physical work put girls at risk of curvature of the spine, and that really they should focus on learning how to be mothers and homemakers (try telling that to Kathleen Drew-Baker, Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Beatrice Shilling or Danielle George).

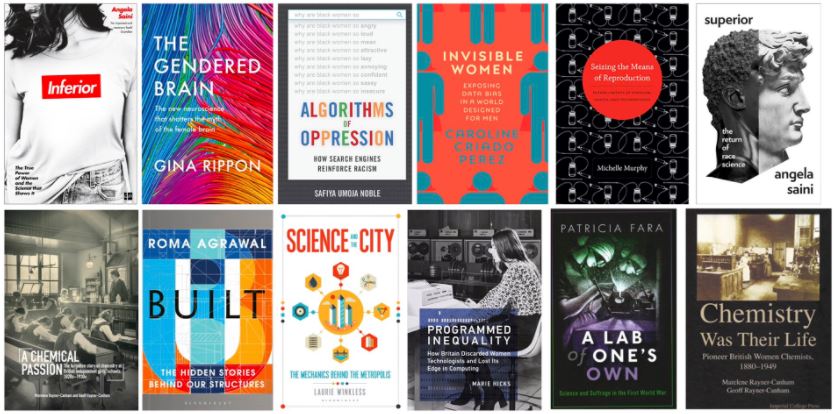

*You can see more of Dr Wade’s book recommendations in the image above.

What the world gives to girls

Dr Wade points to this as an example of the “massive impact” of education policy. “And so too does everything that we give young children and the way that we treat and think about young women,” she adds.

Whether it’s boys’ t-shirts emblazoned with “Little scholar” while girls’ t-shirts say “Cutie Pie”; Lego City (aimed at boys) that allows kids to build infrastructure in miniature, while Lego Friends (aimed at girls) comes with figures that are too big for the scale of the buildings in order to create space for eyelashes and lips on their faces; or that, of the most popular kids’ books published in the Times 100, only 19% have a female protagonist (and fewer than 1% have a main character from a BAME background) – from the earliest age girls are instilled with very different values to boys.

“You pick up the things the world puts in front of you. So if you’re endlessly presented with a group of pink toys, if you’re not told to play around with things, if you’re given books where you’re never represented and you never see anyone who looks like you, that really really impacts how you feel and have confidence in yourself going forward,” says Dr Wade.

A better balance in STEM

The underrepresentation of women in science only continues after school – from bias in the allocation of grants, to men having a greater chance of their papers being accepted and cited. But, together, the scientific community can make a change. This isn’t a problem that will be solved by a handful of wonder women, but by all women of STEM working together.

Dr Wade suggests mentoring others – or finding a mentor; opening up and talking about mental health; investigating sexual harassment; nominating scientists from under-represented groups. “The only people who have the power to change the pattern is us.”

Ultimately, Dr Wade urges the scientific community to “be brave and speak truth to power” – not to be afraid to call out inequality, bias and untruths wherever they occur.

This International Women’s Day, let’s be proud of being part of something bigger – by working together, the balance can be better.

Words – Hayley Cox

Images – The University of Manchester, Joe Shervin, FriendsBricks